[On Monday, January 4th, 2009 I attended an event, hosted by the Washington Project for the Arts, about arts coverage. The event was stimulated by Jessica Dawson’s recent article in the Washington Post, and pursuant responses, including by me. I brought my computer, and sat in the back of the room recording as much as I could of the conversation. The following is not a real transcription. But with the corrections and additions I received I’m encouraged to see that much of the event is captured in the words below. Any mistakes or mis-attributions are mine. As Kriston Capps wrote in a blog post some time ago: “I should emphasize that unless you see two of these— ” —you’re ultimately reading what I got out of it. So let’s nobody mistake my observations for proof of whatever your beef is.” – R. Bettmann]

Running for cover(age): A panel discussion on arts criticism in the DC area

Moderator: Kriston Capps

Panelists: Jeffry Cudlin, Isabel Manalo, Danielle O’Steen

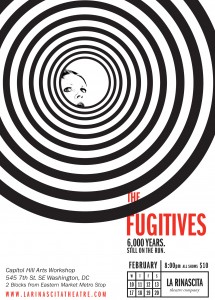

When: Monday, January 4, 2010 from 6:30-8:00pm

Where: Capitol Skyline Hotel (lounge), 10 I Street SW, Washington, DC, 20024

(Free and open to the public)

Lisa Gold: This event was stimulated by an article in the Washington Post about Mera Rubell’s visit to a group of artist studios. The coverage reported some statements by Mera about the isolation of Washington’s artists. There have been a lot of responses to the piece in various online forums and social media sites, including about arts coverage in general, problems with it, critical discourse, and what we should do about it. We welcome all of you here tonight, and are grateful that so many of you showed up to discuss these issues. Just briefly, I’ll introduce the panelists, and moderator.

The moderator is Kriston Capps, a blogger and journalist who writes about art, music, and politics.

Jeffry Cudlin – artist, curator, critic, writes for citypaper and blogs at hatchets and skewers.

Isabel Manalo – au professor, represented by addison ripley, creator of thestudiovisit; her discussion on facebook (on the studiovisit.com page) really sparked this event

Danielle O’Steen – capitol file, art + auction, wash post express., also student in art history @GW specializing in modern art

K: I’m a little under the weather, which is too bad…. Even before this was announced I got an email from someone telling me that they were glad to hear I was moderating this panel, but that they had attended the same panel five years ago and nothing had changed so they wouldn’t be attending… (laugh) I know this kind of conversation has happened before. Washington has grown since I arrived here in 2002. The Do-It-Yourself art events and small spaces have grown and changed. As an aging critic those things are hard to keep up with… With Mera’s visit it was hard to say which Washington she was trying to keep up with: the Dupont circle and Bethesda galleries, or the broader scene. Which brings us to the question: how does journalism reflect this community today? Does it reflect it? I’ll start by saying that the Washington area sees coverage in the post, the citypaper, dcist, express, allournoise, byt, and many blogs – too numerous to mentions. My question is: where is there a lack? Where are things falling through the cracks?

J: As an occasional writer, artists, and curator: from all those standpoints I have different perspectives, or opinions. I am a jack of all trades… I’m an artist myself, an arts writer, and a curator. Basically I want people to write about art for two reasons: criticality and promotion. To move beyond self-satisfaction and move the discourse forward you need criticism. To get butts through the door you just want the coverage, too. There’s not a lot of real analysis happening right now, and there’s no one I would want to single out to do that. In terms of the actual coverage: I write occasionally for the city paper and I’ve seen the coverage shift to 250 word – or shorter – blurbs.

There’s tons of blogs all getting the same press releases and republishing them, but that isn’t the same as more in depth criticism. Frankly its sort of like: “did the Washington Post reviewer show?” And if they didn’t, then the event didn’t really happen. At the same time, lots of the Post pieces are presenting the public with a jazzy punchline to pull in readership highlighting something pretty simple. It really sort of is like, “Did Michael O’Sullivan or Jessica come in?”

There’s the real question of, can you be a professional critic anymore? Self satisfying and self-sustaining? It’s not like there’s a wall there, but as a journalist it’s hard to get pieces, and hard to get visibility and analysis. Both journalists and artists want the coverage. As a critic and an artist it’s a resume line to be published.

K – for Isabel: Do you think anything is being lost in the coverage?

I: There is a diverse range of what’s being written and how it’s being written about. Can there be something that could be addressed there? I think about the hierarchy that exists within the criticism for this city… I think we need more critical venues – beyond the blogs – to dilute the power the Washington Post has. I have more questions than answers. The reason why I started studiovisit.com was to open the door to consider the process, which can then inform my opinion of the artistic object.

K: For critics we want to go in and see objects but we’re supposed to be hands off of personal coverage…

I: For me perhaps its about connection toward understanding, rather than coverage. I’m not a critic but when I do critique what’s helped me to understand the work is getting to know the process behind the art object towards analysing the content and it’s context. The studio visit is not a critical forum, yet. Perhaps having that kind of connection might/would inform how they review work.

K: Someone might take away the sense from the conversation on your site that artists feel isolated. Do you feel that?

I: There is a huge difference between isolated and isolation. Isolation is a self-imposed being alone. Isolated implies a greater external factor forcing an individual or group outside the mainstream. It’s the feeling of being marginalized. I feel both. Rubell’s insights didn’t surprise me about sensing isolation from District artists. We are living in very different spaces and it’s essential if not inherent to being a good artist that we feel “isolation and loneliness”, as Mera states. However I do NOT feel isolated in my community. I feel the opposite.

K – to Jeffry: Do you feel isolated?

J: As an artist I don’t feel isolated, any more than geographically. It’s hard to find studio space… spaces tend to be pretty tucked away. The work is isolating in the sense that we work in these little places and need time to do that. Depending on what position one occupies we have a different answer… you can say there’s 100 galleries in dc or you can say they’re 12 and we’re both right. Lots of us are very invested. I only write about museums 4 times a year cause I’m also involved in trying to get people into shows. One of the questions I have – regarding the coverage, is about whether or not there a way to develop more rich, meaningful, content. So much of the coverage is amature, or extended event listing.

I: This discussion tonight really began on a social media site. How has social media changed criticism. We live in a culture of the ‘like’ button, but no ‘dislike’ button. On Facebook the space between artist and critic has shrunk. I wonder if there is an obligation to perpetuate the virtual “friending in the physical” which may lead to a lot of false positivity toward each other. How does this affect writing critically?

K: Is there any way to help one another? Is there something to criticism feeding community? As a writer we’re all kind of lonely hunters, finding and pitching, and writing our pieces.

J: We see each other at night at opening after opening. Who is our audience? Are we writing for each other, or for the gallery owner, or for the audience we don’t know? We do feel like we have to be self-sustaining and self-promoting. As a writer you want to interest people and engage not just people who would be reading anyway. You don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings.

K: A lot of people write critical/investigative features… which you have to keep at arm’s length.

M: I think it’s ok to get upset, and also to start discussions…

K: Do you think the arm’s length is more of a problem here in dc?

M: No, I just think it’s more apparent.

K: In comparing New York and D.C., Mera gave me a strong sense of a huge bell curve gap between the artists she’s met and the artists at the National Gallery. It’s pretty profound how large that divide is, and how much of a looming presence she saw that to be.

D: I don’t think there is an impenetrable force here. There are so many artists struggling to get through in New York, too.

K: … and we’ve seen shows at Gagosian that are similar to museum.

D: I don’t think DC has to become New York. It’s a different animal. A different machine.

J: The DC Art Scene is like a ladder with all the middle rungs missing. Someone told me that. I think it’s a ladder with two sets of rungs missing. There seems to be no clear path from a to b to c. From getting into a larger institution that supports artists, to finding gallery representation, to “I want to be written about by someone who actually sees.” And Arlington Arts Center is trying to do that. There are a number of local institutions trying to do that.

Galleries and non-profits exist for different reasons. I think about “why does that show exist”. You can do things at non-profits that don’t have to sell. Shows should exist for different reasons. If I want to convince a gallerist to want something, how do I do that if I’m not making traditional object/drawing things?

K: Because of the way our municipal and cultural centers are created there’s an interesting parsing out of Silver Spring/Arlington/Reston/Rockville… of different communities. Do DC’s geography and disparate community organizations affect our overall community?

I: I don’t think New York is any different. There is Chelsea as the center of the art market, but in terms of the local arts community in New York most of it is not in Chelsea. There really are lots of different places. I find it exciting that we have the diversity here and not just giant warehouses all over the place.

K: I think it takes one small pot and puts it into many smaller pools…

J: it makes it a little tricky when you’re coveting people who are doing things somewhere else. I strive to program a particular kind of contemporary art. I think it makes it difficult when you have a lot people who see you a certain way and you may not think of them in that same way. I think there’s a fear of programming an artist at more than one place locally in one year… I think you can get a kind of critical mass… and if there’s different things you’re attempting… if there’s clearly definable reasons some gallerists are able to accept artists being in multiple places at the same time.

K: So you think the area is big enough to support an Arlington arts community, and a Bethesda arts community….

I: I think the federal institutions can play a role galvanizing things together. For instance the Corcoran show a little while ago that featured local contemporary artists. Should the Smithsonian institutions have an obligation to connect to the local community? There’s the artists’ residency at the Hirshorn… is it enough to only have one artist a year?

D: If everything is separated you’re gonna lose something in the mix. I don’t want necessarily a Chelsea, but something that shows DC’s strength. I think certain elements are missing. An auction. An art fair. Not that we need that. I actually missed the DC Art Fair, it happened before I arrived. Not that we need to mimic Miami etc. but you need something to attract collectors. To bring the market for a global/national art scene.

An audience member: There’s a difference between where people make art, but Mera’s reaction was partly to the geographic isolation of the studios which is in fact not uncommon to many communities. In terms of a center of gravity to where studios are located or where galleries are showing…

K: We talked a little about what artists do, and need to do. What about what writers do and need to do? Do New York publications shut the door on non-New York coverage?

D: I have to admit that when I was editing in New York I didn’t want to cover dc… I think it’s a matter of pushing as a freelance writer. You’re also following/fighting with your colleagues for a story. I think for New York magazines a lot of them are really suffering. And there are alternatives for coverage, but I’m personally very attached to magazines and hand-able publications, and I think I’m not alone.

K: At the guardian there was an absolute blood-letting at the end of this past year. I still have connection there, but it’s not what it was. They’re simply not listening as closely to what’s happening over here. Is it important to have coverage in the big glossies?

D: As a writer, I was always nervous about writing or introducing a new artist to the public…. You want to write something meaningful….

K: Does it mean the same if something is reviewed in the Post or on the web?

I: There’s a history with the printed paper… you can talk about the Post and everything else. When I was preparing for a class I went and looked back through old papers. There is something about local magazines — Chicago has a great local culture, and magazines which feed into the national scene. There’s a bit of a micro economy with that.

J: There’s something about print that you can hold onto. To be published like that… it makes artists feel better about the themselves. Similar to us creating our little objects and hoping someone will buy them… Is it meaningful outside of gallery culture?

K: Our editors are trying to push to the web to capture new audience.

D: Magazines and online versions are not the same. Not the same attention to detail or value to each word. Most of times when I write something for online publication it’s not touched. Being edited is encouraging. When you’re not touched, especially for online publications, there’s a sense that maybe even the editor isn’t reading it.

V: I’m a little frustrated I feel like we’re dancing around an issue. Was this inappropriate coverage? Should studio visits for an auction be covered? It was great publicity move by WPA but the writing was mean-spirited and sycophantic. We’re kind of dancing around: was this even news?

K: I felt this was news-worthy. I found out about it, pitched it to my editor. I needed an angle. I got one, they took the piece, and that was that. With any story there can always be questions about editorializing… People may ask about whether the coverage, or the opinion, is warranted or not.

M: The Rubell’s really do have this power when they walk through a space, in Miami, New York, or DC. The phenomena of her coming is just a huge deal. It is news-worthy. The question is in how the story was framed.

I: There’s a larger thing about the dialogue we want to be involved in – in terms of arts dialogue. It’s not that way with the Times in New York. We worry locally because we want people to have read about the show. But in terms of what happens in Art Forum… what we want is to get more involved in these broader conversations.

D: I write for the metro express. There’s a hope of getting out to the larger world, not just the art world.

K: How do you access the art community? I read what I read. And I read Art magazines cover to cover when they arrive and I care about what I read deeply. But I’ve never met another subscriber to Art Papers (big laugh). But in this room there are lots of Post subscribers, or at least readers.

Jayme Mclellan: I think we are moving away from a place where the Post is the only venue. But right now they do have a huge amount of power and influence. It’s dumb-founding. The problem I keep having… A friend of mine said that the Post in the arts section keeps telling you how the game of baseball is played, over and over. We want people to understand, but they dumb it down more and more. There’s not any meat. And that’s what the dc arts community is getting served by. I hope for reviews, and I want that critical dialogue in the paper. But there’s no way to control it.

J: I think the Washington Post is written for readers at a 6th grade level… The City Paper is more for someone who’s had a year of college and is now drunk somewhere… more elevated dialogue and a few jokes thrown in. But even if something is killed in the Post it’s noteworthy.. it helps get people in the door.

Another audience member : With the decline of coverage in the country it’s encouraging to have any coverage. There are dumb and great pieces. And it’s great to have this community brought together in that way.

K: Journalism lost 45k jobs last year. That’s some steel mill kind of stuff right there.

I: Media has to exist but the question is how can the artist benefit from that kind of writing? I sympathize with the Post in that they have to ultimately sell the paper, but there must be a way to write their reviews that connect to the artist community in a constructive way.

D: It’s general interest… What is our reason for writing, and what is your reason for making things? Are stories always covering the negative aspect of things? Why do we write? Why do we create? Do they need to be together? Is the purpose to uplift? To bring down? To sell stories? To sell art?

K: As journalist its not my job to create community. I have to sell papers…. Part of what made the story is that Mera is a great white shark.

I: We had a real opportunity to hear a collector’s voice and we may not like what we heard, but we did hear something.

D: Is the article interpretation? Or was it the story? But was it accurate? Was it her opinion? Every paper wants an angle. Something edgier, tougher to read, cause that’s what people want to read. I try not to get too invested in what I write because every editor has a completely different style. I have to internalize what that is and send my work to the one editor that it’s right for.

J: Editor’s can help you shape that.

K: You need to be your own editor because once you send it out you can’t control what happens to it.

Holly Bass: Editors tend to slant toward the snarky and the negative. It’s hard not to toe that line. I’m aware of that bias and it helps me nagivate a little better. Mera was only supposed to pick twelve artists, and she picked sixteen. Which is great. And that wasn’t talked about a lot. I’d compare DC to Brooklyn over Chelsea. For my friends in Brooklyn it sucks and is incredibly difficult — rent is high, there arent’ many show opportunities…

K: Which brings up the question – we do we think we should we appear at the National Gallery, or the Philips collection?

Ryan Hill: We need to create a mythology around where we live. There are grad students here and, after school, they leave. They go to New York because they think it’s better. But it’s not.

Audience Member: I am on the board of an arts center in Rockville: Metropolitan Center for Visual Arts. We can’t get anyone there to review our shows, and we can’t get anyone there to see the shows. The bottom line is, if we don’t get people out there, we don’t get artists noticed…

K: There are some tips to getting coverage… As journalists we do pay attention to each other. We’re each other’s audience (as far as we know.) For organizers it can be a frustration but the question is who should I get attention from and start there.

Audience member: It would be nice to go a little deeper, not just try for superficial coverage though… The analogy of the ladder.

— At this point I stopped taking notes —

Experimentation was the common thread throughout the construction of this piece – in concepts, in the studio, and in performance. It can be very difficult to just let things happen by accident, but I have come to believe that those unplanned moments are the key to innovation. I had decided that we would have a set – not just a blank stage – and as we progressed in the studio, we experimented with creating different types of physical environments. This involved trying out different groups of materials to create the look and feel of a landfill. In the end, we found that covering the space with newspapers gave the desired effect. Though the cataclysmic volcanic eruption and the landfill in Manila were the starting points for the project, the process of experimentation helped me reveal how these two mountain events are related.

Experimentation was the common thread throughout the construction of this piece – in concepts, in the studio, and in performance. It can be very difficult to just let things happen by accident, but I have come to believe that those unplanned moments are the key to innovation. I had decided that we would have a set – not just a blank stage – and as we progressed in the studio, we experimented with creating different types of physical environments. This involved trying out different groups of materials to create the look and feel of a landfill. In the end, we found that covering the space with newspapers gave the desired effect. Though the cataclysmic volcanic eruption and the landfill in Manila were the starting points for the project, the process of experimentation helped me reveal how these two mountain events are related. As a member of the Earth Savers Dreams Ensemble, Jason traveled across Asia, the United Arab Emirates, Europe, and the United States. In 2001 he moved to New York City to further his studies and expand his experience. He received a scholarship from Ballet Hispanico of NY, a fellowship from the Ailey School, and apprenticed for the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. In 2004 he toured nationally with the Martha Graham Ensemble and performed principal roles, including the Penitent in El Penitente and the yellow couple in Diversion of Angels. In 2008 Washingtonian magazine named Jason Garcia Ignacio one of Washington, D.C.’s Top 20 Showstoppers and in 2009 Jason won the Mayor’s Arts Award for Outstanding Emerging Artist, and the 2009 MetroDC Dance Award for “Outstanding Individual Performance.” Also in 2009, Jason also received the “PEARL Cultural Heritage Award” from the Embassy of the Philippines for his outstanding and meritorious contribution to raising awareness of and deepening appreciation for the Philippines and its rich and diverse culture and heritage through excellence in the field of performing arts. He is a member of the critically-acclaimed CityDance Ensemble, a contemporary dance company based in Washington D.C. (www.jasonignacio.com) and teaches at the CityDance Center at Strathmore.

As a member of the Earth Savers Dreams Ensemble, Jason traveled across Asia, the United Arab Emirates, Europe, and the United States. In 2001 he moved to New York City to further his studies and expand his experience. He received a scholarship from Ballet Hispanico of NY, a fellowship from the Ailey School, and apprenticed for the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company. In 2004 he toured nationally with the Martha Graham Ensemble and performed principal roles, including the Penitent in El Penitente and the yellow couple in Diversion of Angels. In 2008 Washingtonian magazine named Jason Garcia Ignacio one of Washington, D.C.’s Top 20 Showstoppers and in 2009 Jason won the Mayor’s Arts Award for Outstanding Emerging Artist, and the 2009 MetroDC Dance Award for “Outstanding Individual Performance.” Also in 2009, Jason also received the “PEARL Cultural Heritage Award” from the Embassy of the Philippines for his outstanding and meritorious contribution to raising awareness of and deepening appreciation for the Philippines and its rich and diverse culture and heritage through excellence in the field of performing arts. He is a member of the critically-acclaimed CityDance Ensemble, a contemporary dance company based in Washington D.C. (www.jasonignacio.com) and teaches at the CityDance Center at Strathmore.