This article was selected as a finalist in the 2013 DC Student Arts Journalism Challenge, an annual competition designed to identify and support talented young arts writers.

There are many excellent reasons for an all-female production of Julius Caesar. For one, the play is among Shakespeare’s most male-dominated, which is saying something; out of roughly forty characters, only two are female. Those two exist to give (ignored) advice to their husbands, and are saddled with lines like “Think you I am not stronger than my sex?” Furthermore, female friendships are often still trivialized in today’s media, while the shifting alliances, betrayals, and dilemmas seen in Julius Caesar are the stuff of literary legend. It would be great to see a more nuanced portrayal of ‘backstabbing’ among women, without the usual high school movie cattiness. Yet for all of the interesting ways Phyllida Lloyd could have explored gender in Julius Caesar, her sold-out production at London’s Donmar Warehouse fell strangely flat.

Not that there wasn’t plenty of excitement to be found. Even before the first lines of dialogue, the creative team made it clear that this was no ordinary Shakespeare production. Audience members who failed to miss the security cameras lining the walk to the auditorium couldn’t ignore the stark interior of the auditorium: never has the Donmar Warehouse looked so much like a warehouse. Designer Bunny Christie replaced the comfy seating with hard plastic chairs and gave the performance space a dingy, industrial look, complete with peeling paint. A strange array of props litter the stage, from a baby doll and a tricycle to a cake and a paper crown.

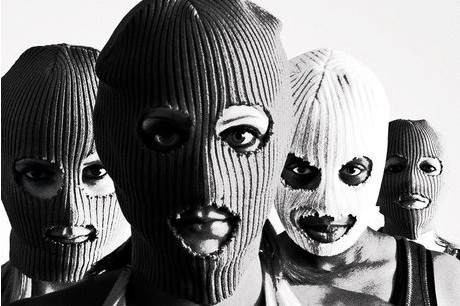

Lloyd’s concept sets the action within a women’s prison, the ‘inmates’ performing the tale of Julius Caesar ala Marat/Sade. The show begins with the framing device of the prison guards unlocking the doors, leading the inmates onto the stage, lining them up, and locking them in. The play itself is filled with loud punk rock music, water guns, and contemporary touches like magazines, doughnuts, and the occasional f-word dropped amid the blank verse—not your grandma’s Shakespeare. The personalities of the prisoners occasionally intrude through their Roman characters, most notably when the murder scene of Cinna the Poet gets out of hand, injuring an ‘actress’ and sending the cast into a frenzy. But Lloyd seems to have little to say with this concept, besides giving excellent female actors the chance to speak some of the Bard’s greatest words. Rather than put a feminine spin on the story and characters, the proceedings all seem very gender-neutral, even butch.

Almost every character wears baggy prison polo shirts and sweatpants—except for Brutus’ wife, Portia (Clare Dunne), dressed in a pretty white dress, and appropriately coded as a ‘female character.’ When she doubles as Octavius Caesar, she, too, wears the shapeless uniform. Some moments simply don’t make sense. Why is the Soothsayer portrayed as a naked child? If Caesar is openly dating Antony, who does Calpurnia represent? If Caesar doubles as a prison guard, why does she wear the prison uniform? Does the metaphor of prison emphasize any aspects of the text, or is it just an arbitrary reason for an all-female cast?

The actors handle the text well, despite the clumsy framing device. The only misfire comes from Frances Baker as Caesar, whose boisterous, loud, and crude, mannerisms don’t seem to come naturally to the veteran actress. She brays her words with elongated vowels, as though sucking the juice out of them as she speaks. It is easy to see why Caesar’s friends would want to stab her; not so much to see how she became so respected in the first place. Maybe it’s the doughnuts she brings the inmates.

The excellent Dame Harriet Walter plays Brutus at least as well as the RSC’s greatest men, with a restrained, haggard demeanor. She even swears in a thoughtful manner. Walter’s gaunt face and gravelly-yet-posh delivery give her an androgynous elegance, and she emphasizes the divide between Brutus’ private turmoil and public stoicism. Her performance is most poignant in a scene where, drifting to sleep in her tent, she dreams of dancing with her dead wife. The play’s most haunting scene and one of its simplest, it hits a level of emotional engagement with the audience that much of the play fails to deliver.

For most of the play, Walter shares the stage with Jenny Jules’ volatile Cassius. Jules spits angry words through her teeth, resembling a rattlesnake as her body shakes with rage. Her Cassius is an exhausting person to watch, both for the audience and for Brutus: Walter seems to grow ten years older when interacting with her. Brutus’ exasperation plays well off of Cassius’ petulance, but Jules lacks the manipulation that Cassius requires. Lean and hungry she certainly is, but subtle, she is not. Clare Dunne’s Portia emphasizes her shared traits with Cassius—she gives herself a ‘voluntary wound’ to prove her bravery to her husband, a moment that takes on greater significance when Cassius attempts to do the same after Portia’s death, and Brutus hastily prevents her. Yet Dunne’s Octavius Caesar seems dull-witted, lacking the spark that make her Portia so interesting.

Cush Jumbo gives Mark Antony nuance from the start, her large dark eyes simultaneously calculating and soft. As Caesar’s toy-girl, she raises the energy whenever she takes the stage, filled with that “quick spirit” that Brutus mocks, but Jumbo moves with a contained grace. Her anger is much quieter than Jules’, and the more threatening for it. Even her acting, though, cannot justify Lloyd’s decision to have her deliver her ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen’ speech lying down.

Other standouts in the cast include Charlotte Josephine as Brutus’ mischievous young servant Lucius and Ishia Bennison’s sarcastic and cackling Casca. This adaptation manages to convey the full story with only fifteen actors, a mean feat for a play with so many characters, and though it is occasionally difficult to tell who was who, the plot itself remains crystal-clear. A battle scene cunningly uses lighting, rock music, and stylized movement to represent Cassius’ decimated ranks: standing on a moving platform, Cassius watches in despair as her soldiers disappear. The assassination scene fills the stage with well-choreographed chaos, forcing Caesar into a chair in the audience (at this performance, mine—I was brought up onto the stage by an actress and placed in the middle of the madness) and shoving bleach down her throat. Rarely, however, does the action attain the electricity that the setting demands. Performed in one act without intermission, using the guards’ interference following the ‘Cinna the poet’ mob to transition across the skip in timeline, the play drags despite the abridged script.

Though this noisy production says little about gender besides showcasing female talent—and Harriet Walter seems ready to conquer Rome, following an enchanting stint as Cleopatra opposite Patrick Stuart—it sparked enough controversy to convert any skeptic to feminism. Cranky critics mocked the idea of an all-female cast more they did any directorial weakness, and droned relentlessly about Shakespeare ‘spinning in his grave’ at the thought of (gasp) female actors! The original text of Julius Caesar is packed with anachronism (characters talk about clocks and doublets, both definitely not Roman, and use Elizabethan slang liberally) yet modernizing Shakespeare’s already-modernized retelling happens surprisingly rarely. Lloyd’s Caesar could have used a bit more substance to back its considerable style, but it certainly injected some fresh spirit—and estrogen—into one of the starchier plays in the literary canon.

Megan Fraedrich is a rising senior Literature major at American University, focusing on early modern drama. She is an avid participant in the campus Shakespeare troupe, the AU Rude Mechanicals, and hopes to direct her own production of Julius Caesar next year. Megan enjoyed a semester abroad in London this past fall, where she got to stand on both the Donmar Warehouse and Globe Theatre stages.

Megan Fraedrich is a rising senior Literature major at American University, focusing on early modern drama. She is an avid participant in the campus Shakespeare troupe, the AU Rude Mechanicals, and hopes to direct her own production of Julius Caesar next year. Megan enjoyed a semester abroad in London this past fall, where she got to stand on both the Donmar Warehouse and Globe Theatre stages.