Mark Morris caused quite a stir when, in a December 2005 New York Times article, he dismissed the necessity for a college level education for modern dancers pursuing a performing career. “Most of it in my opinion is just a big bag of wind,” he said, “I mostly think it ruins people.” He went on saying, “[As for] the .001 percent of people who graduate and become dance professionals, hurray for them. They are very lucky. I think most often it’s in spite of school.” While I don’t share Morris’s extreme pessimism, I think it is unrealistic to expect that the academic system alone can cultivate the passion, imagination, and skill necessary to pursue a dance career.

I do not believe that a university education is at odds with dancing professionally. Professional artists are finding homes in university settings and populating their companies with college level graduates. Five of Morris’ dancers are graduates of Julliard. As a graduate of the University of Utah modern dance department, I represent the small minority that went to college and onto a profesional performing career.

I received a well rounded education in dance and liberal arts that contributed to me becoming a viable professional in the field. My courses in pedagogy and kinesiology have served me well in my career. But it is the breadth of my training – including, prior, and subsequent to my university experience – that I credit for my accomplishments. And I would be remiss to overlook the role of luck, determination, and talent in my success.

I attended a workshop on integrating professional arts into a university environment at the Association of Performing Arts Presenters conference in New York this past January. One presenter described a study of engineers who were found to be less creative when they came out of school than when they went in. I don’t know which school or what methods were used to measure creativity, but I buy the possibility and would posit that the same could be true of a dance student’s college experience.

In college, you learn all the rules; how to do it “right”. Success is rewarded with an “A”. However, that “A” or the level you achieved in college can have little bearing in the “real” dance world. In the arts it is often the people who break the rules with aplomb who get the breaks. Unfortunately, in acquiring tools and techniques, I’ve seen students lose the part that makes them unique. So how do you teach the rules and how to break them? How is success measured in the dance departments? Who is doing the measuring and by what standards?

As an artist in residence, I have taught across the country at liberal arts colleges and universities, including University of Maryland – College Park, University of Maryland at Baltimore County, and Virginia Commonwealth University. I am currently in a visiting artist position at Columbia College in Chicago. Through these experiences I have found that each institution is different. Likewise, MFA, BFA and BA degree programs have different requirements for entry with the intent that they produce different outcomes. For my purposes here, I will address undergraduate programs in liberal arts colleges.

Dance departments are often in the business of selling their programs. Success is determined in part by reputation, location, money and politics. What kind of student do they serve and what kind of dancer do they want to produce? What kind of faculty do they want to attract? Sometimes the answers come from the top down. The culture of a department can be influenced by the passions, priorities, and personality of the head of the department, and whether or not they have the vision, leadership, and strength to forward their agenda and maneuver among the even higher ups. There may be unspoken rules and priorities about what equates success. Does the department value creativity or technical proficiency, generalization or specialization, rigor or nurture, theory or practice, classical repertory or avant-garde? While these concepts are not mutually exclusive, a department can’t be everything to everyone, and someone has to pay the bills.

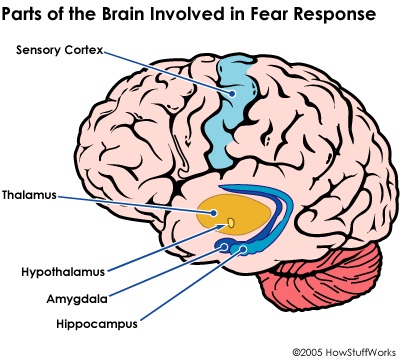

Students also have their measures for success and can have strong opinions about what they need to learn and how it should be taught to them. While many will say they are pursuing a degree because they LOVE to dance, I often see FEAR as a motivator, or rather, an inhibitor. Behind those blank stares is an inability or unwillingness to take risks, a sense of entitlement, judgment, resistance, and self-doubt. Perhaps fear is determining factor that limits creativity. Fear of judgment, fear of failure, and fear of being irrelevant seem to be part of the culture. I find this to be true of both the student population and the faculty (especially if you don’t have tenure!).

However, isn’t the same true for real life? Fear holds so many of us back. So maybe it’s not the college experience at all that makes us lose creativity, just the loss of innocence and the acquisition of experience. I went to college because I was “not ready to go to New York”. I was not ready to be a part of the professional dance community, which was, at least in my mind, unkind, and unforgiving. I didn’t think I was good enough. There were those that argued that point with me, but I wanted more training; to be better prepared. I expected my college experience to educate, not deflate. And it did. Magically, I thought I was “ready” after my sophomore year in college. It was more of a feeling than a logical reason that I can articulate. I’m sure the faculty had their own opinions. Maybe I wasn’t so much “ready” as I was “less afraid”.

I do think there is a generational difference between students now and students 10-15 years ago (MTV generation, what’s valued in the field, what’s valued in the entertainment industry, etc), but I know I was guilty of a few blank stares in my day. There were times when I got by with good enough. I can’t point to the moment in my dance training when I began to understand what the teacher meant when they said I needed to perform in class; when I stopped trying to be “right” and started to investigate intent; when I became more interested in the process rather than the product. Eventually the sum of my training made it click. I do remember one of my most rewarding class experiences was toward the end of my senior year, and I took my technique class pass/fail. I felt such freedom. There’s something to be said from taking class because you want to, and not because you’re supposed to.

Is it possible to create that sort of freedom in the academic setting? How do we encourage risk taking, curiosity, and investigation among students and faculty? How do we not train the passion and creativity out of the students? How do we create cutting edge performers with well versed bodies and intellects?

My approach is to put art first. I am committed to making, creating, and facilitating dance. I tell the students that they are responsible for their learning and that I am available to facilitate that as much as possible. I tell them, “If you’re bored, it’s not my fault”. Some think they used to be better dancers before they started training at the university. I ask them to take responsibility for that. Contrary to how this may sound, I care very much about my students. I make a sincere effort to provide them with the best training and the most opportunities possible.

Supporting the faculty in their art-making, risk-taking, and professional growth is equally important. Sabbaticals, professional development, research and performance opportunities, scholarships, and a solid infrastructure reflect that support. Guest artists, a culturally and stylistically diverse population, a flexible and relevant curriculum, small classes, etc. can all contribute to a very enriching, vibrant, and low stress dance department. Sure, that takes money, and every department has different needs and resources. But sometimes it’s not about money.

When the college, the dean, the head of the department, and the faculty reflect a commitment to put art first, the students will notice. But even then, the student has to want it and sometimes that still is not enough. How do we encourage them to pursue their love of dancing and prepare them for the big bad world of professional dance when less than 1% will make it? If that is the case, what are we preparing them for?

Dance has always been my metaphor for life. It is the one place where I can be unafraid. I had to learn that. My training ultimately gave me that confidence. The more confidence I had, the less fear I felt, the more possibility I found in my dancing – what a wonderful cause and effect. Ultimately, that is what I am preparing them for – life. My job is not to predict which student is going to become a professional dancer or a dance enthusiast. My goal is to teach toward possibility. If a student’s academic training can teach them how to suspend judgment and navigate fear, then that is a degree worth having, despite the odds.

Gesel Mason is Co-founder and Artistic Director of Mason/Rhynes Productions (www.mason-rhynes.org) and Artistic Director for Gesel Mason Performance Projects. Ms. Mason has performed with Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, Repertory Dance Theatre of Utah, and for four seasons with Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, where she continues to perform as a guest artist. Ms. Mason’s solo project, NO BOUNDARIES: Dancing the Visions of Contemporary Black Choreographers, includes the work of Donald McKayle, Bebe Miller, David Rousséve, Andrea Woods, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. She graduated from the University of Utah with a BFA in modern dance and Teacher’s Certification in Secondary Education. She has been an artist in residence at numerous schools and universities across the country. Ms. Mason received a 2007 Millennium Stage Local Dance Commissioning Project from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and will premiere the work August 30 and 31, 2007

Gesel Mason is Co-founder and Artistic Director of Mason/Rhynes Productions (www.mason-rhynes.org) and Artistic Director for Gesel Mason Performance Projects. Ms. Mason has performed with Ririe-Woodbury Dance Company, Repertory Dance Theatre of Utah, and for four seasons with Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, where she continues to perform as a guest artist. Ms. Mason’s solo project, NO BOUNDARIES: Dancing the Visions of Contemporary Black Choreographers, includes the work of Donald McKayle, Bebe Miller, David Rousséve, Andrea Woods, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. She graduated from the University of Utah with a BFA in modern dance and Teacher’s Certification in Secondary Education. She has been an artist in residence at numerous schools and universities across the country. Ms. Mason received a 2007 Millennium Stage Local Dance Commissioning Project from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, and will premiere the work August 30 and 31, 2007

What an excellent piece. I’m sure arts faculties of all disciplines would do well to heed this advice. I wonder if students are going into dance degrees expecting that the degree will magically transform them. One thing that’s not mentioned here is what happens when a dancer’s career must suddenly end due to injury or unemployment? Without a college degree, how can they transition to a meaningful new career?

I had to come back and comment on this again, because it really stayed with me and I felt that as a dancer with a degree and an educator, you simultaneously captured how I’ve gotten to this point in my life and why I educate.

I’ve realized from reading this that I don’t want fear to be a motivator in pursuing dance – the fear of “I don’t know if I’ve done enough with my career, therefore I’m afraid to do something else.” I want the love of the art to be my motivator. This has really helped me come to terms with my own fears.

I teach dance, not just to teach steps, but out of a want to inspire and empower the next generation. Dance class can teach the discipline and social skills that many kids have very little of due to increased use of technology as a communication medium. If you’re only teaching the steps, you’re missing the point.