I love what can happen in Contact Improvisation (CI) dances – especially a kind of exquisite cooperation. Finding that cooperation is not inherently hard, but it can be elusive. It’s often not obvious how the dances are created, even to the dancers, themselves. Descriptions and observations that focus on the dancer’s overt actions and skills can be confusing. Perhaps the key is understanding cooperation. I suggest that cooperation emerges from the partner’s shared focus. A route toward understanding that cooperation is to understand the following:

Contact Improvisation is an exploration of the question, “How can we share balance through change, playing with what happens along the way and allowing that to influence how we continue?”

In the basic CI recipe, dancers follow shared points of contact to discover their dance. By mutually following and investing their balance in shared points of contact, dancers yield independent control of the dance, committing to mutual choices and responses in the moment. This balance sharing is an avenue to vital cooperation in the moment, enabled by the willingness and craft of the partners.

Balance is one of the most pervasive, viscerally compelling ways that we’re involved with the world. Our sense of well-being is legitimately coupled with it, and sensing, processing, and responding to it has an overriding priority in our moment-to-moment awareness. In CI dances, sharing the processes of balance while moving, or even while mostly still, is an opportunity to engage with another person in something that is inherently immediate, and compelling.

By “balance”, I’m referring to all of the senses by which we are aware of and navigate our situation in space. Rather than static equilibrium, it is the process of responding to and playing with the changing conditions of equilibrium while moving together. It’s not staying on-center, but rather continuing to engage with a shared center as the situation develops, however near or far from equilibrium the shared center goes.

Shared changing balance can entail shared paths through space, falling together, lifts and leaps into the air, fluidly shifting responsibilities for (fluidly shifting) shared weight, and much more. It need not include any outwardly overt activity, as well – all of the shared balance can be happening in subtle inter-responsiveness of the partners, in barely noticeable movement. The immediacy of this connection, whether physically in contact or not, fosters a shared sense of presence and liveliness, a process of doing something together as an organism.

In a CI dance (and probably most collaborative improvisation) the relationship between dancers is a dynamic, evolving thing. To maintain integrity in their movement – and their immediate well-being – each partner must distinguish what the commitment means for them in the moment, balancing their independence from and inter-dependence with their partner(s).

Shared, shifting balance is by no means unique to contact improvisation – it’s a fundamental element of most partner dance. Waltzing, for example, fosters elegant connection through this dynamic, in a very clearly delineated form. Many other practices involve it, including not only other forms of dance but also sports, martial arts, and even some meditative arts. Exploration of balance-sharing dynamics is more directly the focus of CI than in most practices, however, over a more open range of activity.

CI dancers are constantly negotiating balance not just of their physical selves, but also of their independence from and inter-dependence with their partners. Paradoxically, development of solo ability is as important as partnering to development of cooperation. Independence vs inter-dependence with your partner is a dynamic balance. At any moment you can overshoot in either direction. Relinquishing too much of your solo sacrifices a dimension of your personal involvement, and presents your partner with too little of your personal substance to engage with. Holding on too tightly to your solo, on the other hand, can preclude responsiveness to your partner, also limiting connection.

In general, developing solo presence and appetite – the ability to find movement that suits you with conviction in the moment – broadens and tunes your options for navigating each dance. You’re freer to develop each connection to the degree that suits you, avoiding the need to force connection in order to sustain your personal momentum. That ability also helps in navigating a Contact Improv jam – a freewheeling event where people explore CI dances. The more options that the participants have for dancing – including dancing solo and in larger ensembles, as well as the more common duets – the more chance that the jam can become a vibrant event.

There is an essential connection between surprise and discovery in any creative endeavor. As Isaac Asimov puts it: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’ but ‘That’s funny…’” In collaborative art, partners depend on common ground to base their mutuality. They need not stay in the familiar, but are most vitally engaged when they grow the new out of the familiar, together. Our sense of well-being is coupled with our sense of balance, for legitimate reasons. In CI we yield control of our balance (in many ways) to share it with another.

In this realm, the consequences of many choices are shared. This adds another dimension of balancing: each partner, individually, negotiates an internal frontier between new and familiar ability. Staying too much with what’s familiar limits discovery, while abandoning discretion can overreach beyond what is tenable. Somewhere in the balance is the frontier of discovery for each person.

It is not for one partner to dictate where the other’s frontier is, and vice-versa. The partners engage best by leaving room for one another’s discretion, exploring together the combination of their choices. This is a kind of etiquette of necessity, so that the intuition and judgment of each can be fully realized in the collaboration. It is how safety is maintained and mutually supported, while exploring frontiers. Like other commitments in this practice, it is a continually fluid balance, reassessed and renegotiated moment to moment by the partners, within themselves and between them.

One type of response that limits ones ability to maintain a fluid balance is “clenching.” Drunks and infants tend to be less injured by catastrophic falls than other people. Due to obliviousness, they are less likely to present themselves as rigid and, therefore, brittle on impact. They are less likely to clench. Clenching is not only a physical response – it is an unwillingness to handle surprise. Responding by clenching often reduces effectiveness by refusing to engage the situation. It also reduces familiarity that would be gained, for next time, through active involvement. In this way, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of ineffectiveness. I believe that measured, deliberate engagement is where the real benefit of training lies. Even in martial arts, the raw experience gained in mock confrontation is probably more important than the particular techniques being explored.

CI is often taught with specific techniques: physical exercises and skills that indicate essential ingredients of the practice. Many interesting questions arise in this approach. For instance, is some particular range of skills necessary to dance CI? Do skills help foster dances, or can they get in the way of some kinds of connections by which the dances cohere? What skills are and what skills are not crucial? I believe that these questions, in themselves, are illuminating, and that the proper response is not cut and dried.

For example: I happen to be partial to falling as an element of dancing. Falling together is an extreme case of sharing dynamic balance, and is exciting and engaging. And yet, some of my most memorable, viscerally involving experiences dancing have involved hardly any movement. It was the level of shared focus and connection that made those dances so memorable – I don’t know what role technique played in them. It was as much not-doing as doing that enabled them to be so deeply realized. Where exactly is the supporting technique? Sometimes it is clear, and sometimes not.

There may not be quick or easy answers to these questions, and I certainly don’t have them. They are revealing, however, of the framing of the practice – some things we take for granted, and some things we can question. My ultimate concern is with what helps me connect and find dances that work. Skills can help lead the way to connection, and help to develop and navigate the dynamics – yet it is the dynamics of cooperating, and ultimately the connection itself, on which the dance thrives.

I’ve found it valuable, in my practice and teaching, to recognize that finding my way into a dance is as central to the art as exploration of the connection once I get there. Personal presence in the moment is a rich and inexhaustible endeavor. The process of finding one’s way there with another, and the process of exploring that terrain together, are each engaging and challenging in themselves. It helps me to recognize this because I can wind up spending as much or more time searching for connection as I do playing in connection. It’s tempting to try to avoid the gaps of the search by instead depending on technique and/or routines that have worked before. Using previous actions this way is trying to “play the same way twice”, foregoing the opportunities of the pursuit of surprise and discovery. Conversely, recognizing and exploring the art of the search is part of discovering presence in the moment, and can inform and support one’s ability to dance as much as anything else.

Embodying presence in the moment and proportionately trusting to share it, learning to non-verbally communicate and connect with immediacy and clarity, navigating and balancing the dynamics of collaboration and commitment in all their intricacy, all these are rich realms explored in Contact Improvisation, and all are enlightening in their discovery.

Ken Manheimer is curious. A software developer by trade, he loves to explore, invent, and move, and enjoys contact improv as a rare combination of these things, and an antidote to the static of everyday life. He has been a member of the D.C. Contact Jam for 20 years. This piece is extracted from writings on Ken’s website, www.myridicity.net.

Ken Manheimer is curious. A software developer by trade, he loves to explore, invent, and move, and enjoys contact improv as a rare combination of these things, and an antidote to the static of everyday life. He has been a member of the D.C. Contact Jam for 20 years. This piece is extracted from writings on Ken’s website, www.myridicity.net.

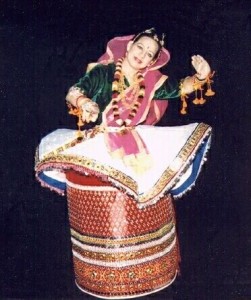

The Shelter Project will premier at Dance Place on May 12 & 13, 2007. Visit www.bosmadance.com for more information. BosmaDance is a contemporary dance company based in Northern Virginia. Founded and directed by award-winning artist Meisha Bosma, BosmaDance was featured in the January 2007 edition of Dance Magazine as one of 25 premier up-and-coming companies in the nation. For the past five years BosmaDance has presented an all-female lineup to reach both youth and adult audiences in the metro DC community through performances, movement workshops, and collaborative performance projects. Meisha Bosma has won five Metro DC Dance Awards for her artistic contributions to the community. Her choreography has been commissioned by the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, Alexandria Performing Arts Association, Virginia Commission on the Arts, CityDance Ensemble, Arlington Arts Center, and universities throughout the country. As a performer, Bosma toured internationally with Kombina Dance Company based in Jerusalem, Israel from 2001-03. Named as one of the capital’s “most powerful women” by Washingtonian Magazine in June 2006, Bosma continues to challenge the public with her distinctive and daring style.

The Shelter Project will premier at Dance Place on May 12 & 13, 2007. Visit www.bosmadance.com for more information. BosmaDance is a contemporary dance company based in Northern Virginia. Founded and directed by award-winning artist Meisha Bosma, BosmaDance was featured in the January 2007 edition of Dance Magazine as one of 25 premier up-and-coming companies in the nation. For the past five years BosmaDance has presented an all-female lineup to reach both youth and adult audiences in the metro DC community through performances, movement workshops, and collaborative performance projects. Meisha Bosma has won five Metro DC Dance Awards for her artistic contributions to the community. Her choreography has been commissioned by the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts, Alexandria Performing Arts Association, Virginia Commission on the Arts, CityDance Ensemble, Arlington Arts Center, and universities throughout the country. As a performer, Bosma toured internationally with Kombina Dance Company based in Jerusalem, Israel from 2001-03. Named as one of the capital’s “most powerful women” by Washingtonian Magazine in June 2006, Bosma continues to challenge the public with her distinctive and daring style.