I’m blessed to have a private studio for my personal use in the home of two of my tango students. They live near me, and the 15-minute walk through a tree-lined, residential area of NW is a calming preparation for creative work. Their studio itself, with its wall of windows, is also a peaceful space to focus.

Time is an under-celebrated luxury, and having this space without the constraints of a typical shared studio schedule has contributed to my creative process, which is first and foremost about listening. On one level, it is listening to myself, honestly asking what it is that I have to say right now, at this point in my life. On another level, it is listening for a match between what I feel compelled or inspired to say, and what I see in the world around me. Without a connection to audiences, to communities, to countries even, I lose motivation. The sense of purpose returns when what I hear from my own inner spaces is echoed in my community or in the world around me.

Right now I am developing a piece around the tango embrace: its shape, its function, how it feels, how it looks, the space it creates for the two people who experience it in dancing the tango and what that space holds or excludes. Every time I begin a project there is a sort of incubation period before an actual name or story comes. I’m in this awkward period right now, and so in the studio what is coming out is very fragmented. I have an ipod playlist with a handful of songs that I am drawn to, including modern tangos by German and American composers and an Italian pop song by Gianmaria Testa. Physically, I have a handful of body shapes and short sequences that feel satisfying but very abstract, and an imaginary image of black fishnet fabric that wraps the upper body and a flowing skirt short enough to reveal the feet, which I realize I need to show in order to express some of the tiny gestures of tango footwork.

Right now I am developing a piece around the tango embrace: its shape, its function, how it feels, how it looks, the space it creates for the two people who experience it in dancing the tango and what that space holds or excludes. Every time I begin a project there is a sort of incubation period before an actual name or story comes. I’m in this awkward period right now, and so in the studio what is coming out is very fragmented. I have an ipod playlist with a handful of songs that I am drawn to, including modern tangos by German and American composers and an Italian pop song by Gianmaria Testa. Physically, I have a handful of body shapes and short sequences that feel satisfying but very abstract, and an imaginary image of black fishnet fabric that wraps the upper body and a flowing skirt short enough to reveal the feet, which I realize I need to show in order to express some of the tiny gestures of tango footwork.

I am taking ballet classes to strengthen my sense of the arms, a part of the body that is usually out of focus in tango, but which now I am giving particular focus to in an exploration of the embrace. The word for embrace in Spanish is abrazo, which translates literally as “to the arm.” I’ve taken “Abrazo” as my working title, but I’m quite certain it will change. I imagine articulated arm movements by three, four, or six dancers in unison, and the same gestures in duet, creating a more elaborate architecture of embracing than one might see in a traditional tango dance, but which tells the story of what that embrace means to the couple. Of late, however, I’ve caught myself doing frappes to tango music while I watch students practice in my tango classes.

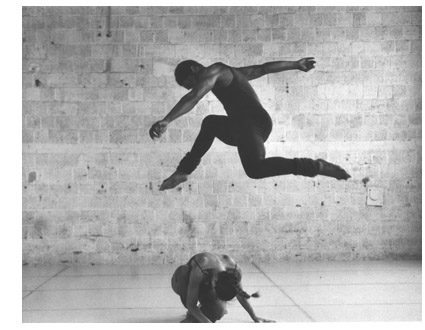

It’s so uncomfortable, this phase of the work. I see pieces of things but don’t have the narrative yet that will provide the logic of the piece. I know there will be several parts, at least one duet, at least one solo, and several sections of ensemble choreography. I want to know who the characters are, but so far the performers in my head are still just abstract dancers in black fishnet with precise arms and long, curving bodies. Their skirts fly behind them as they jump and twist. They are women, fierce and soft at the same time. I play with leading and following roles a lot, since they are important to the tango, and so I imagine some role-changing in the duet section or sections.

It’s so uncomfortable, this phase of the work. I see pieces of things but don’t have the narrative yet that will provide the logic of the piece. I know there will be several parts, at least one duet, at least one solo, and several sections of ensemble choreography. I want to know who the characters are, but so far the performers in my head are still just abstract dancers in black fishnet with precise arms and long, curving bodies. Their skirts fly behind them as they jump and twist. They are women, fierce and soft at the same time. I play with leading and following roles a lot, since they are important to the tango, and so I imagine some role-changing in the duet section or sections.

I’m also writing, right now, as a method of finding a narrative path for this piece that will make creating the physical choreography logical in my own mind, fun even, if still challenging. The writing is like a treasure hunt through the forest, with characters sometimes materializing slowly, shimmering into being, and at other times leaping quite suddenly out of the bushes. I try new movements on myself in the studio, then in later rehearsals teach them to the dancers, then adjust, alter, expand on, and make variations of them in the dancers’ bodies. “Try this” is something I’ve heard myself say a thousand times. It seems that almost everything is a “Try this” at first. My biggest challenge is to be ok with the unknown, to trust that the mist will clear over the lake, and to accept that the most efficient way for me to move along in the process is not to force the end result, but rather to let it unfold in its own way.

[editor’s note: here is a video clip from Sharna Fabiano’s “Uno”, performed by Sharna Fabiano and Francesca Janacek in 2007.]

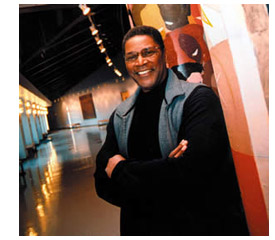

Sharna Fabiano has a background in classical and contemporary dance, and began her Argentine tango career while living in Boston in 1997. In 1999 she co-founded the Boston Tango School and over the next several years made five visits to study tango dance and culture in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She has been educated in several traditional social tango styles by some of the greatest names in the modern Tango Renaissance, and is regarded as an innovator who has remained connected to the tango’s roots while exploring its ever-changing modern aesthetics and vocabulary.

She visited Cuba twice as a guest artist on a US-licensed cultural exchange in 2002, and following that relocated to Washington, DC where she had taught hundreds of students to dance social tango. In 2003, Sharna joined TangoMujer, an all-woman tango dance company based in NYC. TangoMujer is internationally acclaimed for choreography that incorporates theatre and modern dance, and for exploring lead and follow roles between women. In 2006, she established Sharna Fabiano Tango Company in Washington, DC. Sharna has performed at the prestigious Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival and in dozens of European and North American cities. In DC, she has danced at the Argentine Embassy, Lisner Auditorium, and Kennedy Center Millennium Stage. She has produced two of her own evening-length shows at Dance Place, and has participated in the Dance DC Festival, DC Improv Festival, and Hispanic Festival.

In 2008, Sharna was selected for Dance Magazine’s prestigious “25 To Watch List” and featured in the Washingtonian’s October Arts issue as one of the city’s “Rising Stars.” She was also honored by DC’s Filmore Arts Center as one of Washington’s most accomplished artists, and selected to show an excerpt of her all-female trio, “Uno,” at the Festival Cambalache in Buenos Aires.

Sharna is internationally recognized for her elegant, powerful dancing and for her expertise in both leading and following roles. Her choreographic works are inspired by the transformative power of human connection and community found in the tango world. Her written articles on the depth and mystique of social tango have been widely read and translated into several languages, and she has been interviewed for tango publications in Germany, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic.

Photographs of Sharna Fabiano by Christopher Alvanas