This article is the winner of the 2018 DC Student Arts Journalism Challenge.

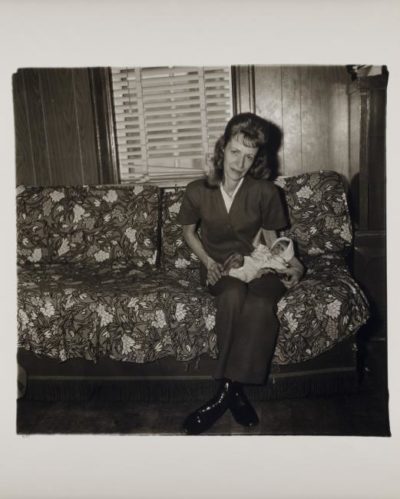

In her brief 12-year career (from her first contracts in 1959 to her death in 1971), Diane Arbus attracted controversy that few photographers ever dream of. Despite being born into wealth, Arbus made her impact photographing people on the margins of society: Children, people with growth disorders, transgender people, nudists, and other “curiosities” of modern society. Arbus was known for her elaborate portrait staging; she would take dozens of photos of her subjects until she found an angle and a pose that she found engaging. This lead to numerous reactions, from interest from the public, to anger from subjects, to criticism for over-sensationalizing. Arbus’s legacy is well-known for toeing the line between acceptance and ostracization, humanity and voyeurism. The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition Diane Arbus: A Box of Ten Photographs does the same, at times alternating between intimacy and detachedness, and integration and removal.

A Box of Ten Photographs is Arbus’s only portfolio, a collection of ten large-size photos she sold to four different patrons before her death. The Smithsonian’s collection belonged to Bea Feitler, and includes an eleventh photo, as Arbus noted on the album’s cover, by crossing out the “Ten” and replacing it with “Eleven.” (figure 1)2. In the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the setting of the exhibition is odd: Arbus’s voyeuristic album is situated between the Presidential Portrait Gallery and an exhibit on the natural beauty of the American West. However, the Arbus exhibition’s consecutive three-room design leads well into the exhibit’s linear, chronological theme.

Walking into the first of the exhibition’s three rooms, the viewer is greeted by the album cover. Behind it are four of Arbus’s self-portraits, almost as if the artist is inviting criticism, but ready to turn yet another deaf ear. Beginning on the right-hand wall, a series of dates with accompanying text detail the process of producing the Box of Ten Photographs. Within this timeline, the exhibit features Arbus’s drafting ideas for the album. The exhibit also features some marketing materials used to advertise the collection, with smaller prints of some of the collection’s more iconic works, such as A Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in The Bronx, N.Y. 1970.

As one proceeds to the left and into the next room, one is greeted with the full scale of the album, much larger than imagined. The ten eleven photos circle the room, with two paragraphs of text on Arbus’s final years on the back wall. The photos are displayed opposite Arbus’s commentary, uniformly one-sentence description of the subject, as well as any pertinent information. Here, the exhibition breaks from its chronological theme, allowing the viewer to spend time with each shocking work, to not feel rushed by dates and text.

A common word used to describe Arbus’s work is “intimacy.” Critics claim that Arbus brings the viewer into the photograph, placing them inside the apartment, on the street, or by the side of whoever she is highlighting. But perhaps none does this as well as Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, Long Island. Placing the viewer inside a drab Long Island apartment with an overly gaudy Christmas tree, Arbus departs from her usual theme of people, instead opting to show fringe and abnormality in a different way. But as with so many of her photos, the viewer is left wondering about Arbus’s message. Is she critiquing the family’s spending beyond their means on Christmas decor? Is the featured oddity here the ultra-religious? There is no obvious answer, but Arbus’s work effectively transports the viewer back in time to 1960s New York and lets them imagine the people to whom the tree belongs.

Far from the previous celebration of intimacy, the final room details A Box of Ten Photographs’ rise to international renown, focusing on the 36th Venice Biennale. The visitor’s reaction to Arbus’s work is contextualized with the reactions of those around the world. As Arbus had died the year before, the writings in this room are mostly from her patrons and her daughter, Doon Arbus. They are highly celebratory of Arbus’s life, but with a tinge of sadness and regret over her untimely death.

In whole, the exhibit creates a sense of dissonance and confusion, not unlike the photos featured. The photographs show society’s “abnormalities,” but does specify if they should be embraced or mocked. Likewise, the exhibit presents this dilemma, but does not specify whether Arbus should be seen as a champion of the shunned or as the ringmaster of a humiliating freak show. Box of Ten Photographs (both the work and the exhibit) is a study in duality. Each facet of the exhibit can be seen in two different ways, positive and negative, black and white. The break in the timeline in the central room cracks the linearity of the exhibit, but it also works to highlight the main attraction from the background information. The exhibit, like Arbus herself, provides little in the way of commentary for the pieces, it simply contextualizes them in space and time. There is both too much context and too little of it. A Box of Ten Photographs is highly polished and professional, with each work thrown into large-scale relief – but also hastily sloppy, with text handwritten and full of cross-outs and corrections. In the end, is it good or bad? Is it well constructed commentary or is it just a rich girl mocking those below her? The exhibit curator isn’t telling, and neither is Diane Arbus.

Gabriel Falk is an international affairs student at George Washington University who also harbors a special interest in the arts. Gabriel is a writing consultant and researcher at the GW Writing Center, where he helps other university students to develop their own writing, both academic and otherwise. In his free time, he enjoys photography, writing short stories, and travel in and around DC.