We all know what it feels like to be the black sheep – and we can all recall a time when that’s all we wanted to be.

Think back to your rebellious phase – that time in your life when you felt like Big Brother was out to get you and your parents just didn’t understand (Will Smith knew it best). Mine was the product of a discovery of old-school punk rock bands like the Clash combined with an eye-opening reading of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in my sophomore year English class. Regardless of whether your own period of defiance was spurred by leather-wearing anarchists or peyote-smoking hippies, though, the latest photography exhibition at the National Gallery of Art speaks to the nonconformist in all of us.

The exhibit, Beat Memories: the Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, is a wild and exciting look into the world of the Beat Generation, a group of writers including Jack Kerouac, William S. Borroughs, and Ginsberg himself that became prominent in the 1950s – a time of extreme materialism, fear and conformity in America brought on by the Cold War and the anti-Communist sentiments of Senator Joe McCarthy during the Second Red Scare. Kerouac’s On the Road, Borroughs’ The Naked Lunch, and Ginsberg’s Howl were the major defining works of this generation, one which rejected these modern societal norms and turned instead to experimentation with drugs, alternative forms of sexuality, and Eastern religion. They preached lives of spontaneity, simplicity, and self-discovery, all the while expressing their contempt for the conformist culture in which they lived. Ginsberg’s “Sunflower Sutra” is a prime example of the prominent influence of Eastern thought and philosophy on the Beat writers, who often incorporated the fundamental ideas of Buddhism, Hinduism, and other Eastern religions into their writing as a means of conveying the problems they saw in their contemporary American society.

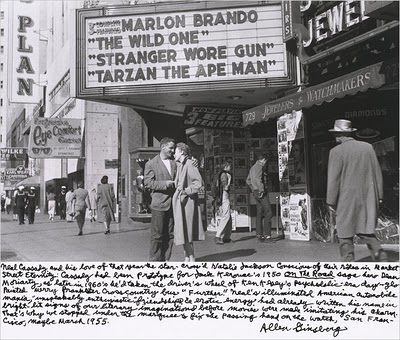

The photos themselves – which constitute the first-ever scholarly exhibition of Ginsberg’s photography – create a fascinating ride through the unorthodox lives of these countercultural icons as seen by the poet himself. For the most part, they are candid portraits of Borroughs, Kerouac, and others, accompanied by a poetic, stream-of-conscious description of the images’ contexts written in Ginsberg’s sloppy scrawl. Together, the photo and the text work like Dick van Dyke’s magical sidewalk chalk drawings in Mary Poppins, allowing the viewer the opportunity to leap right into the scene at hand and be transported directly into the wild world of the Beats.

Upon entering the exhibit, you learn that Ginsberg picked up photography after purchasing a thirteen-dollar Kodak camera at a pawn shop in 1953 (with which many of the early prints were taken). That fact alone speaks to Ginsberg’s style, both as a poet and a photographer; he is at once spontaneous and romantic, aware that the quality of his work comes not from the quality of the materials with which he works, but from his own unique observations of the world around him – and, as one can see after viewing these first few images, he did not need a fancy camera to capture this unique perspective.

Ginsberg once said that “the only thing that can save the world is the reclaiming of the awareness of the world. That’s what poetry does” – and it would appear that that’s what photography does as well. His photographs are simultaneously iconographic and intimate, strange and personal. They capture the Beat Generation’s philosophy of living in the moment while maintaining awareness of the beauty which surrounded them. They serve as instantaneous glimpses into the lives of a group of people who were both disheartened by the society in which they lived, one guided by convention and fear, and enchanted by the world that existed beyond these confines of conformity. They are the graphic version of Ginsberg’s poetry – spontaneous, personal, unconventional, imperfect, and shamelessly honest. They are portraits of iconic, countercultural voices as seen through the eyes (and lens) of another. One of the marks of a successful portrait is its ability to capture the unique spirit and persona of the sitter, and, though he is by no means considered one of the great American photographers, he certainly achieved success in this regard. Through his photography, Ginsberg captured not only the carefree personalities of his close friends, but also the greater spirit of an entire generation of like-minded writers, artists, and thinkers who dared to be different.

So, the next time you’re feeling like just another sheep in the flock, take my advice: abandon the flock. Get off campus, hop on the Metro, and head down to the National Gallery to take a ride on the Beat bus for yourself. This exhibit is sure to inspire as well as entertain and, if nothing else, to remind you to embrace your own individuality.

Clare Donnelly is a junior at Georgetown University studying Art History. A proud native of the Ocean State, she quickly fell in love with D.C. and its vibrant arts scene upon moving to the city for her freshman year at Georgetown. It was not until this past semester, however, that she made her foray into arts journalism, serving as a columnist for The Guide (the weekly magazine for The Hoya, Georgetown’s student newspaper of record). When not busy eating, sleeping, and breathing the arts, Clare also takes part in Georgetown’s New Student Orientation, Relay for Life, and student theater. She is currently studying abroad in Brussels, Belgium.

“Turn on, Tune in..” is one of the five finalists in the 2011 DC Student Arts Journalism Challenge.