That summer, Eleanor Lewis went to Scotland for a month, and I was charged with the care of her house, her plants, and her Jack Russell terrier, Mabel. Mabel was a finicky eater, and I spent much of that month worrying that she was slowly starving to death.

Eleanor’s house was large, immaculately kept, and old. I examined her calendar and grocery lists to divine what kind of person she was; she had an appointment with a woman named Annabelle, and was in need of three garlic cloves, chives, and wheat germ. My Great-Aunt Madeline had asked me to house-sit for Eleanor because Eleanor was boring the ladies in their book club with tales of how impossible it was to find a decent house-sitter.

My summer with Mabel was spent ghostwriting the history of my high school in honor of its centennial celebration. The school was French, old, stuffy, and I was somewhat fond of it, so I agreed to toil away for hours at Eleanor’s dining room table even though another person’s name—an important name—would be printed on the cover. The school, known herein as X, was considering asking a parent who had recently written a very popular biography of Sir Isaac Newton to be the “author” of X, Celebrating One Hundred Years of Academic Excellence. Or perhaps the parent who was the Argentine ambassador. If neither of them agreed, they would ask the great granddaughter of the founder, who was ancient and very, very blind.

Eleanor Lewis’s neighborhood was very upper crust. It was also silent, poorly lit, and it appeared that no one actually lived there. These were estates that the neighbors kept for the sake of keeping estates; I’m sure there is some reason to keep a house that you don’t live in. Perhaps the neighbors wanted to leave their options open. They might decide they did want to live there after all. Perhaps there were too many memories, and they couldn’t bear to part with the estates, preferring instead to turn them into mausoleums commemorating the not-so-distant past. Perhaps these were the houses where they had raised their now-grown and successful offspring, and the neighborhood had once been full of laughter and children cavorting on manicured lawns.

Or perhaps they were all spies masquerading as important lawyers and diplomats and were in various exotic and dangerous locales doing whatever it is spies do. Perhaps Eleanor was a spy. A spy for Scotland. A spy on Scotland. Although she just seemed divorced and well traveled.

It came to feel as though Eleanor didn’t live there, had never lived there. My boyfriend stayed in the house with me most nights, and we began to refer to the house as Mabel’s house. “Do you think we should water the plants at Mabel’s more than once a week?” we would say. “Mabel’s neighborhood is very quiet.” “I locked myself out of Mabel’s house this morning.”

And I did lock myself out of Mabel’s house one morning. Mabel and I had been playing ball in the yard. With Mabel, you always had to play toss with two tennis balls because after she chased the first ball down, she never relinquished it, chewing on it and attacking it indefinitely, which made for a very tiresome game of fetch. Once, she bit my hand when I tried to take it from her. So you had to throw one ball, have her bring it back to you and then throw the other, and she would drop the first. After I grew tired of the game, and Mabel had somehow commandeered both balls, I walked towards the back door. I knew, even before I touched the knob, that it was locked.

“Shit,” I said. “Shit. Shit. Shit.”

I could see my cell phone sitting on the kitchen table. I stuck my head through the doggie door to see if I would fit. I did not. I ran around the front of the house, hoping I had forgotten to lock the front door. I had not.

Mabel and I sat on the front stoop for an hour, waiting  for someone to walk by. Once a week, without warning, an “assistant” came by the house. I hoped that today the assistant would appear. Eleanor referred to her as “the assistant” despite the fact that Eleanor did not appear to be employed. Assistants are for lawyers, I wanted to protest. It seemed like a fabulously luxurious thing to have a life assistant. The assistant went through Eleanor’s mail, and then did something on Eleanor’s computer for an hour. She also bought things for the house like cleaning supplies, dog food, and had some of Eleanor’s clothes dry-cleaned. By nine thirty, I had lost all hope that the assistant was coming, and allowed myself to rest my head in my hands gloomily. Mabel seemed to have lost hope as well, but was too dignified to sulk and lay politely at my feet.

for someone to walk by. Once a week, without warning, an “assistant” came by the house. I hoped that today the assistant would appear. Eleanor referred to her as “the assistant” despite the fact that Eleanor did not appear to be employed. Assistants are for lawyers, I wanted to protest. It seemed like a fabulously luxurious thing to have a life assistant. The assistant went through Eleanor’s mail, and then did something on Eleanor’s computer for an hour. She also bought things for the house like cleaning supplies, dog food, and had some of Eleanor’s clothes dry-cleaned. By nine thirty, I had lost all hope that the assistant was coming, and allowed myself to rest my head in my hands gloomily. Mabel seemed to have lost hope as well, but was too dignified to sulk and lay politely at my feet.

Suddenly, someone came out of the house across the street. She was a middle-aged woman, dressed in a lavender pantsuit, and wore a serious expression. I walked over and explained our predicament, leaving Mabel tethered to the post.

“Where is Eleanor these days?” the woman asked, hanging dry cleaning in her car.

Scotland, I told her.

“I think we may have a key, and if we do, you are in luck because I think we are the only neighbors she would give a key to.”

I wondered if this was because Eleanor knew that the other neighbors were untrustworthy spies.

“I’m Sharon,” said the woman.

I told her my name and apologized for making her late for work.

“No, no! This is important. You can’t sit outside all day.” I decided I liked Sharon, her frankness and her pragmatism. I suddenly did feel important. I had things to do. I couldn’t possibly sit outside all day. Maybe I was just relieved to see someone was living in that neighborhood. I nearly hugged her.

We walked up her front walk, and when we approached the door, she said, “Jeremy isn’t dressed yet. You’ll have to wait in the hallway.” I told her that would be fine, wondering what kind of person Jeremy was that he would be undressed on the main level of the house at nine thirty in the morning. Perhaps her husband.

The house had a cloistered feeling to it, and it wasn’t very presentable. The shades in the library on my right were drawn and gave the room a musty smell. There was a framed painting on the floor leaning against the wall. There were papers all over the hall table, and books and newspapers stacked on the stairs.

“Jeremy,” Sharon called out, “Do we have a key to Eleanor Lewis’s house?”

“Yes,” said a voice from the other room. I thought that perhaps the voice belonged to a surly teenager; he sounded groggy, and from the labored way he spoke, he appeared to be lying down on the living room couch.

“Well where is it?” asked Sharon.

“It’s in the chest in the library.” This time, I knew he was not a surly teenager. In fact, something was terribly wrong with Jeremy. His speech was slurred, as though something was partially obstructing his air passage, and the result was a muffling. Speaking, it appeared, was a demanding task for Jeremy. Perhaps he was some kind of invalid. Or had suffered some kind of terrible accident. Sharon knelt on the ground of the library floor. She had the drawer in her lap and she was holding various keys in her hands.

“Jeremy, which key is it?”

No answer.

“Jeremy, we need your help,” she said, sounding desperate and irritated. “Which key is Eleanor’s?”

“It’s the one on the blue chain,” he said finally. I had dueling urges to walk around the corner and look at Jeremy, naked or not, and also to run from the house. I stayed where I was. Sharon pulled a key out of the drawer and walked around the corner with it.

“Is this it?”

There was a long pause. “Yes,” the voice said.

Sharon waited in her car while I tried the key. It was the correct key. Mabel, who had been waiting dutifully in the yard, jumped around my ankles and scampered into the house when I let her loose. Sharon told me to drop the key in her mail slot and drove off. I walked up her front walk, but the door was partially open. I thought that I should close it, to protect Jeremy. I yelled in the door, “Thank you!” and waited.

No response.

I closed the door and dropped the key through the slot.

Later that night, I told my boyfriend about Jeremy. He agreed that it was strange and sad, and we stared at our plates, sloppy with spaghetti, and thought that there was nothing to do but wonder about the life of an invalid.

A few days later, Sharon knocked on my door.

“Annie,” she said, “Do you think you could come over in the afternoons and let the dog out in the backyard? I normally come home and check on Jeremy, and let Sally out myself, but I’m sitting on a panel all week and won’t be able to.”

I told her I would be happy to help her.

“I figured it would be okay, since you’re in the neighborhood anyway.” I wondered how she knew that I was home during the day if she wasn’t, and told her of course, it was no problem.

“We’ll pay you of course.”

I told her it wasn’t necessary, that letting the dog in and out of the backyard seemed too simple a task to charge someone for.

“Thank you so much. And don’t worry. Jeremy won’t be in your way. He stays in the den while I’m gone.”

“It’s no problem,” I reassured her. I wondered what Jeremy could possibly do all day in the den. I wondered if he had to stay in a single room because he was attached to some sort of machine. I wondered if he had the mobility to move between rooms, or if he stayed in the den by choice. Perhaps he felt safest in the den. Perhaps she didn’t want him wandering around the house in a wheelchair, or whatever kind of contraption he was in, in case he knocked into something and hurt himself. I wondered why they didn’t get a nurse. Perhaps Jeremy had refused the nurse, preferring to be alone. Who wanted a stranger lurking around them all day, anyway? Perhaps Jeremy didn’t want anyone looking at him. Perhaps Jeremy had been like this for a long time, and knew how to care for himself.

Perhaps nothing was wrong with Jeremy at all, he just had an unusual voice. I hoped I wouldn’t see him when I let the dog out. But I also hoped I would. If I saw him, I wanted to look at him in a way that wasn’t objectifying. I didn’t want him to think I pitied him. Although I pitied him terribly. Unless of course, he wasn’t an invalid. But something was clearly wrong. He was a captive inside his own house, possibly inside his own body. I wanted to convey the perfect balance of humanism and unflinching regard. I wanted to look him directly in the eye, as if I spoke to people with crippling illnesses every day, so much so that I didn’t see the illness or the injury. All the ill people I knew were just people to me—legs or no legs, machines instead of lungs or no machines.

Sharon and I walked into her house so she could show me how to let the dog out. I looked around the living room for an invalid. No one. We made our way through the hallway to the back of the house where the kitchen was. There was a room directly across from the kitchen, with a closed glass door and drawn shades.

“That’s the den,” Sharon said. I nodded.

The dog, Sally, was an ancient poodle, and was behind a baby gate in the kitchen. She scratched my legs with her little sharp nails when she jumped on me. Maybe she wasn’t ancient, but just had gray hair.

“You just open this door,” Sharon said, “And let her run around for a few minutes. She usually just chases her tail and barks at it until she gets tired. Then you let her back in, check her water, and put the baby gate back up.”

I told her that I thought that sounded easy enough. She thanked me again and gave me a key.

The next day around noon, I went over to Sharon and Jeremy’s. I opened the front door and called into the house. Sally barked, a high-pitched, yippy little bark.

“Hello?” I said.

No response.

“It’s just me, Annie, from across the street. I’m just here to let the dog out.”

No response.

I walked back to the kitchen. The den door was closed. There was no sound. No TV. No radio. Nothing. I wondered if Jeremy was just sitting in there, blinking, on the other side of the door. Of course he wasn’t. He was probably sleeping. I felt sheepish for trying to speak to him, likely disturbing the few moments of painless rest he could enjoy. Meanwhile, Sally had been leaping in the air for joy, her little nub tail whirling around excitedly like a helicopter propeller. I stepped over the baby gate and let her out into the backyard. She ran around maniacally in circles, and then disappeared into the bushes. The house was silent except for the ticking of an old wooden clock on the kitchen wall.

When I got back to Mabel’s, she sniffed me for a long time. I told my boyfriend about Sharon’s house that night over dinner.

“Did you see Jeremy?” he asked.

“I didn’t.”

“Maybe he’s not there.”

“Of course he’s there. Where would he go?”

I went to Sharon and Jeremy’s every day that week, and every day it was the same. There was no sound except the ticking of the kitchen clock. Every day, I yelled hello to someone who didn’t respond. Every day, I felt sheepish for doing this, but it felt wrong to walk into a house when I knew someone was there without announcing myself. Every day, Sally was thrilled to see me and scratched my legs. Every day, there was no sign of Jeremy. Except on the second to last day, I saw some clear tubing that looked like something you might see in a hospital coiled on the stairs. But other than that, there was nothing.

About a week after Sharon’s panel, I was sitting at Mabel’s, writing at the dining room table. It had been going badly, and I was lonely. I had come to the grim realization that nobody was going to read this book on my French high school, but it had to be painstakingly accurate in the off chance that someone did decide to read it. Which no one would. But someone could. In theory. This mixture of painstaking work and anonymity had become intolerable. Suddenly the phone rang. I had been instructed not to answer it, so I let it ring, as I did every other time it rang, and Mabel barked at the phone as she always did. The answering machine picked up, and I recognized the voice.

“Annie, are you there? Annie, please pick up. It’s Sharon Stein from across the street.” I ran over to the phone and picked it up.

“I just got a call from Jeremy,” Sharon said breathlessly. “Something is tangled in his wheels. He’s upset. I’d help him myself, but I’m all the way downtown, it will take me thirty minutes. Do you think you could go first, and see what the problem is? I’ll head home in the meantime.”

“I just got a call from Jeremy,” Sharon said breathlessly. “Something is tangled in his wheels. He’s upset. I’d help him myself, but I’m all the way downtown, it will take me thirty minutes. Do you think you could go first, and see what the problem is? I’ll head home in the meantime.”

I told her I would go over, that it was no problem. I told her that I could call her once I was there and let her know what the situation was, and perhaps she didn’t need to come home.

“No, no,” she said. “He’s upset, I’m coming home.”

Something is tangled in his wheels, she had said. Oh, is he a robot then? I had wanted to say. His wheels.

I opened the front door of Jeremy and Sharon’s house.

“Hello?” I called.

No answer.

“Jeremy?” I said.

No answer.

I stood in front of the den door, my hand on the knob. I knocked. I hoped Jeremy was dressed. “I’m coming in,” I said. I opened the door slowly, not sure what to expect on the other side, which incarnation of Jeremy. The teenager? The robot?

And there was Jeremy, sitting on the other side of the room. I’m not quite sure how to explain what exactly was wrong with Jeremy. He appeared to be a paraplegic. He could have been in his late fifties, but he was extremely frail, and had no muscle tone anywhere on his body. His neck was very limp and his head was slumped back at an angle that made his expression jarring. There was an IV attached to his left hand, and the hand was curled awkwardly, as if he had some kind of terrible permanent cramp in it. His right hand was also curled awkwardly around some kind of wheelchair controller on the armrest that looked like a little joystick. Out of the center of his neck came a tube, similar to the tubing I had seen earlier on the stairs. I tried not to look at it, or wonder how it was attached to his throat. He looked at me. He had clouded blue eyes, which were blood shot, and he looked directly at me. I had never seen eyes like his, so clouded they were gray and utterly unreflective. I looked down at the floor, feeling as though my breath had been taken away.

The strings of the curtains had gotten tangled in his wheels. These were his wheels. I looked over at the curtains. He must have tried to drive when he got stuck because he had torn the curtains off the wall. They, along with the bar that attached them to the wall, were lying in a heap on the floor. I looked more closely at his right hand. It was scraped and bleeding.

“Are you okay?”

He blinked and stared at me, and then started to make a noise, but his voice was dry, and he stopped. “You’ve hurt your hand,” I said. I walked closer, looking at his hand, until I was standing over him. His eyes fell lazily across my face. He had a portable phone in his lap. The skin on his hand was papery, bruised and looked easily tearable.

“I’m going to get you a Band-Aid,” I said. “Sharon will be home soon.”

I climbed the steps two at a time, looking for a medicine cabinet. I passed by a few rooms. One appeared to be a guestroom. One was a large sunny room with nothing but books and a desk in it. There were books everywhere, books on the floor, books in the shelves, books on the desk. The room by the medicine cabinet was closed. I found a Band-Aid and some Neosporin. I washed my hands, worrying that Jeremy was immune-compromised. I walked back down the stairs, and back to the den.

He was still sitting there, just as I had left him, staring, with the curtains all around him. I walked over slowly.

“I’m going to put the Neosporin on your hand.”

He blinked and watched me, as I put the Neosporin on my fingertip, and applied it to his hand. It felt as I expected it would feel. Papery. Tearable.

Part of me was glad to touch him. To know what he felt like.

After I was done, I applied the Band-Aid, and he looked at me, with his clouded blue, bloodshot eyes. He said nothing, but looked entirely miserable. I imagined he was in great pain. Not from the curtain falling on his hand. But from a life like this. I worked to untangle the cord from his wheels. I worked slowly because I wanted to stay with him until Sharon came home, but I didn’t want to stand in the room alone with him, doing and saying nothing. I had to cut the cord with scissors, it was so badly tangled. I spent some time pulling the pieces out from the wheels, and he just sat there.

Eventually, I heard the front door open. Sharon hurried down the hall. I was sitting on the couch by the window by then. She stopped in the doorway. She didn’t say anything. Her face was serious, and her eyes were watery, but strong. She walked over to Jeremy and softly put her arms on his shoulders and rested her face on his head. She seemed to be smelling his hair, kissing it. Jeremy closed his eyes, looking finally calm. They stayed that way for a long time, clinging to each other. I looked away. Eventually I excused myself, and Sharon and Jeremy seemed to have forgotten that I was there.

“Thank you,” she said matter-of-factly. When I left the room, they were still curled around each other, and she was gently stroking his hair with her index finger. I remember wishing that this were the history I was charged to write, sitting at Eleanor’s dining room table, Mabel at my feet—the history of a man whose life was not always like this.

I never saw them again, Jeremy or Sharon, but I think of them often. I don’t think Jeremy was always that way. I think there was a time when his muscles wrapped tightly around his bones, his voice was strong and resonant, and his hair was blonder and thicker, his skin tanner, less papery and translucent, and he stood in the backyard throwing a Frisbee for Sally, laughing and laughing in the golden summer light. Sharon would sit in a lawn chair on the deck and watch them, laughing too.

Laura E. Smith is a graduate of the University of Virginia’s English program. She is currently editing her novel, So Long, Scout, which was a semifinalist in Amazon’s Breakthrough Novel Award. She is also preparing to open a yogurt parfait bar and smoothie shop called Yola in DuPont Circle in October.

Edited by Jessica Wilde

A Life Like This by Laura E. Smith (c) Copyright Laura E. Smith; printed by permission of the author.

Through The Branches Photo by Michael Drummond; Jack Russell Terrier Photo by Thomas Adamski; Wheelchair Photo by Emmanuel Boutet (Wikimedia Commons)

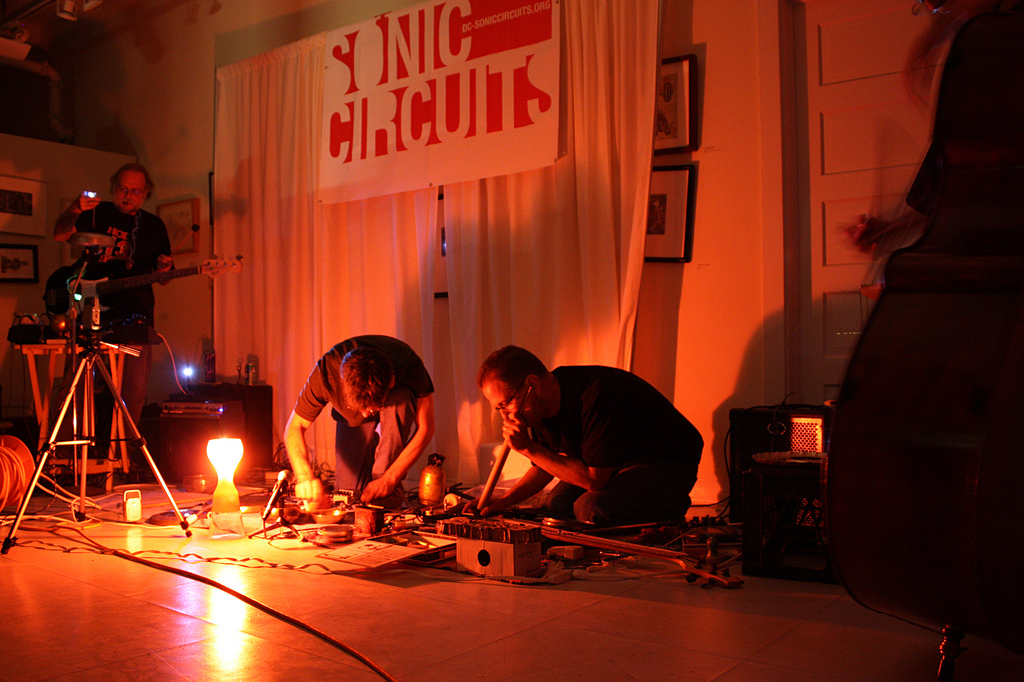

A native of New Haven, CT, Daniel Barbiero has been active in improvised and experimental music in the Baltimore-Washington area for several years as a performer, composer, and ensemble leader. His music reflects his long-standing engagement with scalar and free improvisation, aleatory composition, and alternative methods of scoring for mixed ensembles. His creative activities have included leading and composing for the ensembles Shape Memory Alloy and Third Object Orchestra; he has collaborated with pianist Nobu Stowe and electronic sound sculptor Lee Pembleton, and backed Ictus Records percussionist Andrea Centazzo and Blue Note recording artist Greg Osby. In addition to his work with the Nancy Havlik Dance Performance Group, he currently plays in nine_strings, Liquid Friction Assemblage, and in the ambient/surrealist/improvisational trio Mercury Fools the Alchemist.

A native of New Haven, CT, Daniel Barbiero has been active in improvised and experimental music in the Baltimore-Washington area for several years as a performer, composer, and ensemble leader. His music reflects his long-standing engagement with scalar and free improvisation, aleatory composition, and alternative methods of scoring for mixed ensembles. His creative activities have included leading and composing for the ensembles Shape Memory Alloy and Third Object Orchestra; he has collaborated with pianist Nobu Stowe and electronic sound sculptor Lee Pembleton, and backed Ictus Records percussionist Andrea Centazzo and Blue Note recording artist Greg Osby. In addition to his work with the Nancy Havlik Dance Performance Group, he currently plays in nine_strings, Liquid Friction Assemblage, and in the ambient/surrealist/improvisational trio Mercury Fools the Alchemist.