by Josh Stein

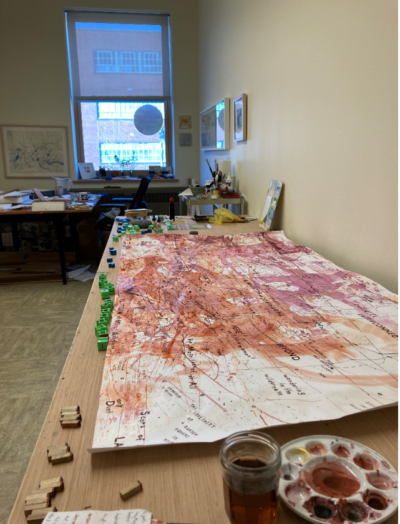

Space in Napa, California is quite dear, so I have always worked in a small corner of my bedroom. While it’s a limited size, 4-by-6-foot space, the vaulted ceiling lets me work with canvases up to 6-by-6-feet. Room is tight, but I organize things in a way that allows me to fit six vertical easels and three flat double-sided worktables arranged around my chair. All of the pieces are mobile, so I can work on more than a dozen large pieces at any one time.

I paint during all available daytime hours (and into the evening when possible), so if something is not going right or I am not feeling a particular piece, I simply move onto another. Over the past three years I’ve progressed from averaging one finished piece per week (working solely in metallic inks), to one piece every three days, to four or five finished acrylic pieces a day.

Storage is my biggest concern, which is why I have rendered many pieces on flat canvas, creating storage in flat-file portfolios up to 18×24 inches. As I learned working in small kitchens, the key to a productive workflow is to clean up as I go and never allow any clutter to accumulate. Every night, I break down my station (including moving anything flat because of my three cats), and I reset the next morning. It guarantees my space is always reasonably presentable, too.

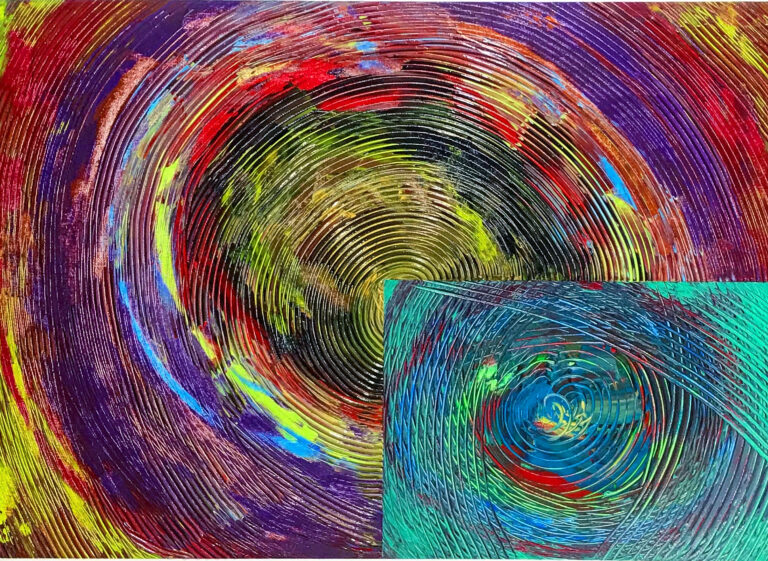

I approach my art with a pretty broad set of tools, including palette knives, cake knives, offset scarpers, toothed combs, cake decorating tools, broad flatbrushes, a giant compass, a heat gun, a hairdryer, and metallic, fluorescent, color-shifting acrylic paints. I primarily paint with palette knives, but I occasionally use brushes for certain pieces.

I start some pieces with a quick sketch; others I lay out grids or curves before adding paint, especially for more complicated geometrical work. A typical piece uses many layers of tape to create particular forms or shapes, which are then painted via knife skimming, or underpainted and dried before a second layer of paint is added inside the same tape form. A comb is used to create texture and patterns within the second layer, allowing the first layer to come through and influence the light and tone of the second. Depending on the piece, this process may be repeated hundreds or thousands of times.

I often work with knives sans hard edge limitations. The skimming takes on impressionistic overtones as the edges themselves become part of the canvas. I try to move as fast as I can, maximizing my painting time even if that means switching from piece to piece.

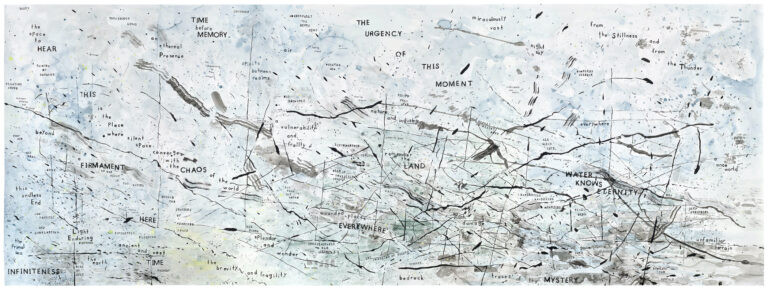

I don’t really have a style, but I do have an approach—to fool the eye and then convince it to participate in the visual experience itself. I liken much of my palette knife’s optical and geometrical work to that of handprinted monotypes. I use a mobile form to create the images, skimming layer upon layer of paint onto taped and re-taped canvas sections.

Most evenings, once the painting is done, I turn to the unglamorous aspects of being an artist: sending submissions; updating databases, image files, and portfolios; emailing clients; maintaining social media; and keeping track of accepted work. At any given time, I have multiple physical and online exhibitions occurring globally. I sell through multiple avenues, including galleries and online portals like Threadless and Etsy. Even though I sometimes struggle to keep up with the business side of being an artist, there’ll always be time to sell my pieces later in life. Right now, my focus is on creating.

Josh Stein is a lifelong multi-mode creative artist, musician, writer, teacher, and adult beverage maker. With formal training in calligraphy, graphic design, and color work; more than two decades as a researcher, teacher, and writer in cultural analysis in the vein of the Birmingham and Frankfurt Schools; and a decade and a half as a commercial artist and designer for multiple winery clients; he brings his influences of Pop art, Tattoo flash and lining techniques, and Abstract Surrealism and Expressionism to the extreme edge where graphic design and calligraphy meet the Platonic theory of forms. The resulting metallic inks and acrylics on canvas delight and perplex, moving between the worlds of solidity and abstraction.

Josh Stein is an artist featured in “Authenticity and Identity”, a visual arts exhibition curated by Ori Z. Soltes on display at Adas Israel Congregation, Washington, D.C., April 6 to May 15, 2021. To learn more about the exhibition visit https://authenticityandidentity.com/.