When designing for dance it is important to always be aware of the movement. Every form of dance has it’s own particular movement flow and uses the body in different ways. I have been fortunate in my experience to have seen a great deal of dance before I was ever asked to design for dance. I will try to give a basic outline of how I work through my design process so that choreographers and designers may have a guide as to how to put their ideas together. Of course, each project must be approached with some degree of individuality, so not all works will follow the same route in their development. The designer and choreographer should always try to make the process a collaboration, allowing each one’s artistic values to be evident. This comes with good communication and a respect for each other’s talents.

To begin, I try to find out what the given are. By this I mean that we settle on what the basic guidelines are for the project – the budget, the deadline, number of performers and pieces of costume that they will need. This will decide whether it is a project that is manageable. Time and money are always important factors.

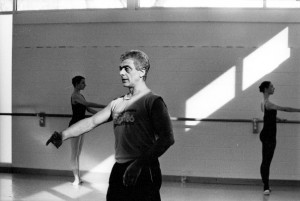

Next is to see the dance. It helps if you can get a visual record. I find it very helpful to be able to see the dance more than once so I can get a sense of how the body is being used. The basic ideas really needs to be there. I do not like to design for works in progress. Doing so is like having to select a frame for an unfinished painting. I think that the stronger the vision a choreographer has, the stronger the design element can be. Here is where I usually clarify with the choreographer what his ideas and intent is for the piece. What ideas or feelings is he or she trying to bring out? What is the mood?

After having seen the dance, as nearly finished as possible, I try to determine a silhouette. I make some basic line drawings to show the shapes that I think will work best with the movement. This will enable the choreographer to decide what direction to take. These drawing should be simple. But they will help determine basic shapes for the neckline, hemline, sleeve length, loose fitting or close fitting. Once the choreographer has decided on the outline, I try to ask about colors. Color is important to set the tonal mood for the piece. Other factors here will be what the lighting and scenics are doing. Make sure the color choices are in harmony with these other essential aspects of a production. I will also make some suggestions as to what fabric choice I think will work with the movement.

I have found that taking the choreographer to look at fabric to be a great help. Most designers will offer fabric swatches (small sample pieces) for a choreographer to choose from. But I find that it is much easier for both the designer and the choreographer when they see the fabric on the bolt. Each type of fabric has its own intrinsic movement and weight. One cannot get a good sense of this from a swatch. Often the availability of the materials may help to determine what the final choice will be. It is at this time that the budget and timeline factor into the final design and ultimately how complicated or intricate a costume can be.

Once materials are chosen I make some sample costumes. This will allow the dancer and the choreographer to try it with the movement and give feedback on what they like and what they dislike. From this information you can make modifications as necessary to move towards the final costume. Make sure to communicate to them what final additions are to be made to the costume before it is completely finished. For example, what kind of undergarments will be used, what closures will be used, jewelry choices, head pieces, make up and hair. These details can play a very important part in the total look of a design.

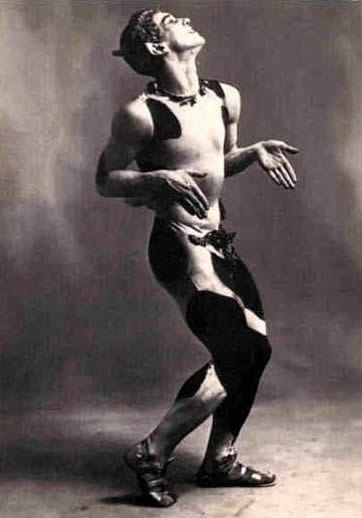

Finally I check to make sure that the overall look is what the choreographer wants. Does the final design add to the entirety of the work? Nothing is worse than to see a costume restricting the dance. The other danger is that a costume calls too much attention to itself such that it distracts they eye from the dance. Design should always serve to highlight the movement not to hinder it.

Sabado Lam has spent twenty years in and out of dressing rooms. He spent many years working for Paul Taylor, a few for Washington Ballet, and now works in several D.C. theaters. In addition to his design work, he earns a living as a wardrobe assistant.

This article was originally published in Bourgeon Vol. 2 #1, September 2006.