Under Cover of Nonsense

You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught

Song from South Pacific

We lived in Milwaukee in the 1950’s

and I learned the ditty when I was

five or six years old.

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe,

Knowing the chant was essential

if I wanted to get the last cookie

or have a turn jumping rope.

Catch a n—– by the toe

We would singsong what seemed

to be silly sounds, made-up words.

Nonsense words in a nonsense rhyme.

If he hollers let him go

It was two more years before I first saw

a Black person. Many more before

I understood what I had been taught.

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe.

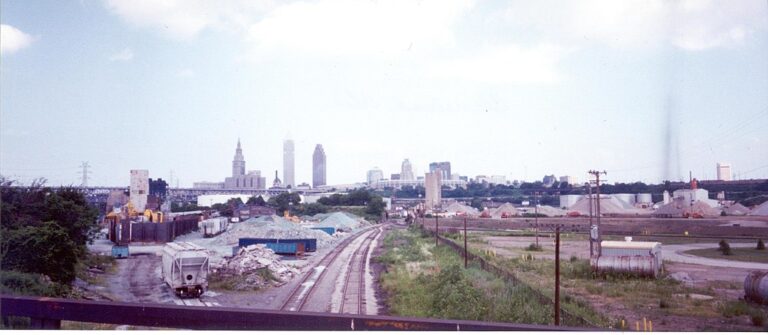

Doris, Just Doris

Adults didn’t have first names

when I was growing up in Cleveland.

Except for one.

Mrs. Williams lived on the east side

of our house and had a dog named Soot.

Mrs. Amato lived on the west and had

black hair that hung to her waist. Mrs. Bernon

lived across the street until she died

in a car crash one moonless night.

Children didn’t know adults’ first names

because we were taught to address them all

as Mr. or Mrs. Somebody. Except for a woman

who came to clean Mrs. Bowerman’s house.

She was the first person I ever saw

who had skin the color of coffee with no cream.

Her name was Doris. Just Doris.

Rebecca Leet spent her early childhood in Milwaukee and Cleveland, assimilating racism in places where she only ever saw one black person. She moved with her family to Northern Virginia in 1961, the early days of school desegregation and a time when non-Southerners asserted that racism existed only in the South.

Image of Cleveland skyline by Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons