In 2007 and 2008, I attended The Laban-Bartenieff Institute of Movement Studies weekend studies program, resulting in my Certified Movement Analyst (CMA) degree. While attending this course, friends of mine would sometimes ask, “What do you do there all weekend?”

Many people know nothing about Laban’s work, and even people who have heard of Laban are easily confused by its complex vocabulary. In answering a question on my final exam I produced this informal and somewhat tongue-in-cheek response to the question.

——

So, you want to know about my adventure with Laban? Well, let’s sit on the porch in the sunshine, have a glass of wine or two, and I’ll try to make some sense out of it for you.

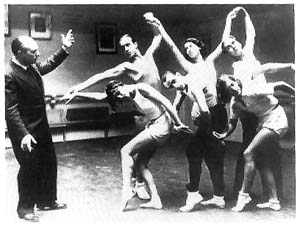

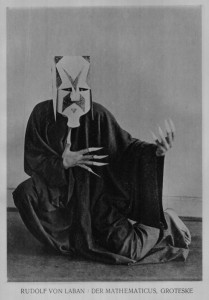

Rudolf Laban was a Renaissance Man, a kind of educated dilettante, who dabbled in the arts and mathematics, and a few zillion other areas. He was fascinated with movement and the human body – in not a simply “theoretical” way. (He evidently had quite the way with the ladies.) Laban had a wife, and many affairs, and obviously a lot of free time in which to develop his theories. I think one of the reasons why he focused his erudition on body movement was to get those women – and men – out frolicking in the nude in nature.

Rudolf Laban was a Renaissance Man, a kind of educated dilettante, who dabbled in the arts and mathematics, and a few zillion other areas. He was fascinated with movement and the human body – in not a simply “theoretical” way. (He evidently had quite the way with the ladies.) Laban had a wife, and many affairs, and obviously a lot of free time in which to develop his theories. I think one of the reasons why he focused his erudition on body movement was to get those women – and men – out frolicking in the nude in nature.

In the early 1940s in Europe, Laban was hired to study factory workers in order to help industry find the most economical movements for workers (in terms of their own bodies and their factory output). He saw that repetitive motions could result in muscle dysfunction unless they were balanced with opposite muscle movements to provide Recuperation. He labeled this series of balancing actions, Efforts. The German word he actually used means “driving on” or an impulse that comes from inside, but he translated it into the English word ‘Effort’. He had difficulty with the translation; maybe that’s why some of what he wrote is so dense and confusing.

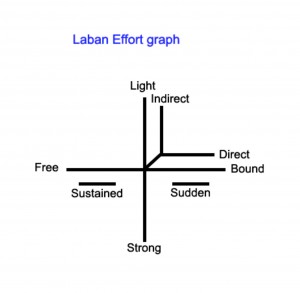

From what he observed, Laban divided Effort into four ‘Factors’: Flow, Weight, Time and Space. Each Factor is comprised of two elements: Free Flow and Bound Flow; Light Weight and Strong Weight; Sustained Time and Quick Time; and Direct Space and Indirect Space.

Flow has to do with whether a movement is fluid or restrained. Free Flow is an action that cannot stop suddenly, while Bound Flow is an action that can be easily arrested. If I’m “holding on” to keep from slipping on ice in my driveway, I’m probably using Bound Flow. If I throw this apple core out into the yard, then I could be using Free Flow.

Direct Space Effort has to do with pinpointing something; so if I point to that cherry tree in the orchard because I want you to look specifically at it, I’d be using Direct Space Effort. But if I want you to get an idea of the scope of our property, I could sweep my arm side-to-side to take in everything, and this would be multi-focused Indirect Space Effort.

Weight Effort seems fairly obvious. I can show you some Strong Weight by pounding on the table. Okay?!?! But, if I brush some of the lint from your shirt, I’m using Light Weight.

Time Effort can be tricky because it doesn’t really have to do with time in “length of time” or “chronology,” rather with how you approach time. (Oh, Laban was big on Intent — all the Efforts have some kind of personal, internal Intent. That has to do with what you want your movement to say and mean. In the end, it’s all about meaning and communication.) I can have an hour to get something accomplished and approach it in a rush as if I have only a minute, in Quick Time; or I can have five minutes to get the same thing completed and approach it as if I have all day, in Sustained Time. What is confusing is that Quick Time is not constant speed; Sustained Time is not constant slowness. It’s about the increasing and decreasing of Time. You can’t “see” Time Effort without contrast. In fact, it’s difficult to specifically pinpoint any of the Effort qualities without contrast because you can see the Effort quality only at the moment it is changing.

Time Effort can be tricky because it doesn’t really have to do with time in “length of time” or “chronology,” rather with how you approach time. (Oh, Laban was big on Intent — all the Efforts have some kind of personal, internal Intent. That has to do with what you want your movement to say and mean. In the end, it’s all about meaning and communication.) I can have an hour to get something accomplished and approach it in a rush as if I have only a minute, in Quick Time; or I can have five minutes to get the same thing completed and approach it as if I have all day, in Sustained Time. What is confusing is that Quick Time is not constant speed; Sustained Time is not constant slowness. It’s about the increasing and decreasing of Time. You can’t “see” Time Effort without contrast. In fact, it’s difficult to specifically pinpoint any of the Effort qualities without contrast because you can see the Effort quality only at the moment it is changing.

So, those are just the very basics of the Effort Factors. Laban’s work also has a connection with the study of Jung’s theories. For instance, Flow corresponds to feeling; Space has to do with thinking; Weight relates to sensing; and Time is involved with intuiting. When I observe movements, I’m trying to make connections between the movement and the meaning — a sort of non-verbal communication theory.

Laban saw innumerable connections between spatial forms and movement, and he observed that certain Efforts occurred in certain spatial configurations. He found that we usually move Upward with Lightness and Downward with Strength. If I reach up to grab something from the cupboard, I’d be going Up with Light Weight; but if I’m splitting a piece of wood, I’d be going Down with Strength. This doesn’t mean that you can’t do the opposite; Laban called these opposites, Disaffinities. I know it sounds complicated. The scary part is that I actually make sense of this, and I’ve been able to use these theories in classes and choreography.

No, we’re not finished yet. YOU’RE NEVER FINISHED WITH Laban Movement Analysis!

Every time you think you know something and understand the concept, there’s another question, and you’re back at square one. And a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. I think that’s why Laban was so dangerous — he had a little knowledge about a lot of things and tried to put them all together in an intelligent (cerebral) way. And, he often did not answer questions directly. I guess that’s another reason why so many people kept hanging around him: they were waiting for an answer, so they thought they might as well have a good time while they were waiting.

Laban decided that identifying these Efforts just wasn’t enough. He had to add them together and come up with what he called States and Drives. States are combinations of 2 Efforts, and Drives are combinations of 3 Efforts. He named all of these, too–6 States and 4 Drives. No, there aren’t any with 4 Efforts (although this is possible); but if there were, you’d probably be in one now because I can see that you may not have been serious when you asked me to tell you what I did in this course. Maybe we could call 4-Effort combinations — Drive Aways!

Laban decided that identifying these Efforts just wasn’t enough. He had to add them together and come up with what he called States and Drives. States are combinations of 2 Efforts, and Drives are combinations of 3 Efforts. He named all of these, too–6 States and 4 Drives. No, there aren’t any with 4 Efforts (although this is possible); but if there were, you’d probably be in one now because I can see that you may not have been serious when you asked me to tell you what I did in this course. Maybe we could call 4-Effort combinations — Drive Aways!

Laban analysis provides insight into the emotional and spiritual values of movement. When I couple the Jungian concepts with Laban’s, I can ask myself questions like: “Is my impact on others Strong or Light?” I can work on figuring out how to express Outwardly what I’m Intending Inwardly by considering the Efforts I am projecting.

I’ve probably lost you by now….. Just remember for the future: if you ask me a question, you are likely to get an answer! If this information piques your interest to learn more about Laban and Laban Analysis, I recommend Karen K. Bradley’s book, Rudolf Laban, published by Routledge.

Cheryl Palonis Adams has an M.F.A. in Dance from the University of Utah, a B.A. in Humanities/Dance from Wayne State University, Maryland Teacher Certification in 5-12 English, and is a Certified Movement Analyst (CMA). Cheryl has taught dance at the University of Toledo and St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and k-12 dance in the private and public sectors. Most recently, Cheryl taught English and Dance for Calvert County Public Schools where she directed the student company, CalvertCrossCurrents Dance and served as choreographer for the Theatre Department. She is a member of the Southern Maryland Modern Dance Collective, serves on the National Dance Education Organization’s (NDEO) Board of Directors, and is the Associate Editor of the Journal of Dance Education (JODE).

Very well done and I learned something too.

Thanks, Cheryl! This is great and JUST in time for the Maryland dance majors to pick up some hints for their final papers in LMA!!

As for my book, yes EVERYONE should buy it! The publisher needs the money! Plus I had almost as much fun writing it as Cheryl had writing this version!!

Very well written! There is much here to think about, and so much potential application, both in singing/acting and “normal” life. Thanks for sharing this!

This is fun, Cheryl! But, hey, as I see it, there are definitely combinations of 4 Effort Qualities–we call them Complete Full Effort Actions! They can be such movements as feelingfully (with Flow) Floating off into a light spacious vast forever for a prolonged nanosecond, or feelingfully (with Flow) violently stabbing someone with a fluid Punch. (Don’t try these while driving or making love.)

Very interesting. I’m very impressed with Laban’s research and theories.

I loved reading this, and I can’t wait to start my CMA courses.

Thanks Cheryl, I’d be particularly interested in knowing more about your application(s) of this work to choreography. I find that our undergraduates have difficulty making the transfer of effort factors to their work–their own choreographic work might be an important connection for them.

This was a very well written, and informative way to describe the methods of Laban. I feel as though each of us could make more of a connection to ourselves physically, mentally, and spiritually if we analyze ourselves with the thought that: “repetitive motions can result in muscle dysfunction unless they are balanced with opposite muscle movements.” Thank you for the chance to break the surface into the world of Laban movement.

Regarding repetitive motions… just was this in a piece from The Atlantic (June ’06):

“Management theory came to life in 1899 with a simple question: “How many tons of pig iron bars can a worker load onto a rail car in the course of a working day?” The man behind this question was Frederick Winslow Taylor, the author of The Principles of Scientific Management and, by most accounts, the founding father of the whole management business.”

Article here:http://www.theatlantic.com/doc/print/200606/stewart-business

Interesting the different directions individuals take with similar starting points.

It is so great to hear a take on Laban that has some humor. I’ve always felt that effort especially was simple and logical and understandable and not all that serious! Thank you, Cheryl. I’ve pared this down and will use it (with attribution) this fall with my high school juniors.