The dance of Isadora Duncan is a crafted study and artistic rendering of the human soul. The technique is based on the free flow and organic movements of humanity’s universal activities: walking, running, kneeling, reclining, skipping, and leaping. For Isadora, presenting the general locomotive movements of humanity allowed for representation of the oneness of humanity.

The simplicity of locomotive movements provides a steady rhythm for the lower body that is then combined with more lyrical expression of the melody in the upper body. Isadora said that her legs expressed the rhythm, and her upper body the melody. In Duncan technique everyday motions are stripped of all artifice – every kink, and every stiffness, every habitual tick are trained out of the dancer’s body. The result is that what the audience sees can appear easy, even though years of rigorous study are required to achieve the effect!

The imagery in Duncan’s choreography was informed by her study of Greek and Renaissance art. Isadora worked to achieve the natural, weighted, strong movements of the Greek figure. She considered the Greek ideal to be the most beautiful because it represented a perfection of the human form. Her dancing was not Greek, but because she felt the Greeks ‘had it right’, she embodied the forms that their art displays.

Isadora found in the solar plexus the “internal motor” of movement. She spent long hours in the studio, hands folded over her solar plexus, waiting for the inspiration for movement. She used the focus of the eyes and the flow in the solar plexus to initiate movement. In performance she would look, breathe, and then move, creating the impression that she had just had the idea to move in a particular direction. Duncan instructors often urge dancers to hear the music and then move. This technique contributes to the illusion of improvisation that exists in Duncan’s choreography. Duncan grandly insisted that she was a visual manifestation of the entire orchestra. From all reports, Isadora was a marvel on stage. Part of the power of her dancing came from her ability to bring a sense of improvisation to the performance of choreography.

Although some of Duncan’s choreographies contain repeated elements from her technique vocabulary (the sway or skip jump, for example), these were executed differently to reflect the music of the choreographed piece. In addition, Duncan used social dances – such as the waltz, polka, and mazurka – in her choreography. For example, the waltz is employed in the tiny jewel dances like the Brahms Waltzes or magnificent showcases like Strauss’s Blue Danube. Even when she used social dance forms, Duncan insisted that dancers move from the solar plexus. She demanded that the dance was a personal expression, even when some motions came from existing social forms.

Preserving Duncan’s Legacy

Isadora died unexpectedly at the age of 49 in 1927. At that time, she was distant from her six adopted daughters (who had formed the troupe of dancers she performed with – the “Isadorables.”) Some of Isadora’s choreographies died with her, but many of the dances have been preserved. Around 200 choreographies by Duncan are still known and performed today.

Three Isadorables in particular – Irma, Anna, Lisa, and Maria Theresa – took up the call to continue Isadora’s work, and honorably worked to ensure that choreographies, technique, and exercises were preserved and passed down.

Three Isadorables in particular – Irma, Anna, Lisa, and Maria Theresa – took up the call to continue Isadora’s work, and honorably worked to ensure that choreographies, technique, and exercises were preserved and passed down.

Today, Duncan Dancers who initially worked just to preserve Isadora’s choreographies are now experimenting with new choreographies in the Duncan style. There is a healing beauty in the pure expression presented in Duncan Dance that is particularly relevant to today’s modern world. The themes of nature and universal humanity that permeate each gesture of the Duncan technique counterbalance the hard lines, rigid expression, and abstract (often negative) concepts so frequently presented in contemporary dance and art.

Much of the world believes that there is no technique to Duncan Dance. They see images of women skipping around gardens, and think “that is not difficult.” This falsity is compounded by the tendency of some Duncan devotees to ignore the discipline required to accurately perform Duncan’s dances. Isadora crafted very specific movements to express the music of her chosen dance pieces and required that the dancer perform them with deeply personal expression.

The Duncan technique is now rather rare in the dance world, especially if you are looking to train with a high quality teacher. While there are several teacher certification programs available through some of the established Duncan foundations, working with a “certified” teacher does not necessarily indicate you are working with a “Duncan Dancer.” In picking a teacher it is advisable to find one who with several specific traits. Your teacher should have:

- years of training with a variety of well-established Duncan Masters.

- be able to trace their lineage directly back to Isadora through the Isadorables.

- be able to speak intelligently about Isadora’s life and philosophy as well as her technique

- have extensive knowledge of Duncan repertory, vocabulary and classwork

The Life of Isadora Duncan

Isadora was born in Oakland, California, on May 26, 1877. She was first and foremost a Californian – she loved the ocean, tall trees, mountains and free spaces of 19th century California. Isadora’s relationship with America was always love-hate. American audiences, except for a brief period in the mid – 1910’s, basically rejected her. It was Europeans who validated her work not just as great Dance, but as great Art.

When money was scarce in Europe after World War I, Duncan moved to Russia. At that time, Russia was in the midst of post-revolutionary efforts to build a utopia of artistry, and there was some promise that Duncan would be assisted in efforts to establish the school of dance she longed for. Funding for the Moscow school was pulled less than six months after she arrived to establish it, however. She lived long enough to see the crumbling of the communal promise. Had she lived longer, Isadora may have rejected the communist philosophy altogether.

When money was scarce in Europe after World War I, Duncan moved to Russia. At that time, Russia was in the midst of post-revolutionary efforts to build a utopia of artistry, and there was some promise that Duncan would be assisted in efforts to establish the school of dance she longed for. Funding for the Moscow school was pulled less than six months after she arrived to establish it, however. She lived long enough to see the crumbling of the communal promise. Had she lived longer, Isadora may have rejected the communist philosophy altogether.

Isadora’s support of the Bolshevik Revolution and Soviet Russia seems to stemmed from a romantic notion of Marxist philosophy, and some bitter feelings of rejection from America. Isadora’s communist leanings had little to do with actual adherence to the politics of communism. But her communist statements contributed to an overall notoriety in Western nations.

Isadora was a revolutionary beyond the world of dance. She adopted a style of dress different than most women of her class, rejecting the binding corsets and high-topped shoes of the Victorian/Edwardian era. Her attitudes about motherhood were also counter-culture: she had three children out of wedlock and repudiated marriage. She was known to drink and party as was only common for men of the day. Combined with her Bolshevik statements, Isadora’s reputation was decidedly wild.

Even today, many people are aware of Duncan’s tragic and bizarre manner of death. Isadora passed away after being strangled and dragged when her scarf caught in the spokes of a moving convertible sports care in Nice, France, in 1927.

Isadora Duncan’s Influence

What Isadora can rightfully be credited with is taking modern dance from a notion, to a place of respect amongst the fine art forms. More than any other artist she brought dance to a place of respect beside literature, painting, music, poetry, and sculpture. Her visit to Russia in 1904 had a catalyzing effect on the formation of the Ballet Russes, and Isadora’s use of music, movement flow, staging and costuming inspired Fokine’s ideas as he began that great company.

She managed the realignment of dance in the art world through several methods. She choreographed and performed to concert music by acknowledged masters, including Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Chopin, Brahms, and Wagner. The relationship of her choreography to ancient Greek and Renaissance art validated the images that she created, and capitalized on the popularity of that art at the time. Isadora also wrote and lectured extensively about dance. Her greatest work, “The Art of Dance”, is a wonderful resource for all dancers, and a fine introduction to all artists as it discusses the theories, impulses, and importance of dance.

After Isadora, dancers were free to dance to the music of their choice, to dance about the condition of the human spirit, and to express themselves, not just a storyline. Isadora was a muse and peer to numerous notable artists of her day, including Rodin, Cocteau, Walkowitz, Stanislavsky, Esenin, and others. She was the subject of countless paintings, sketches, photographs, sculpture, and poems. But her greatest contribution was to the art of dance.

One of the glories of Duncan Dance is that there is no “perfect” body type. No dancer is rejected for being to tall, too short, too long-torsoed, too bony, or too fat. It’s how you dance that mattered to Isadora. In this respect, as in many other respects, Duncan is the mother of today’s modern dance. Though she has been gone for almost a hundred years, the technique, theory, and inspiration that she brought continue to influence generation after generation of artists.

Valerie Durham is a 4th generation Duncan Dancer, and the Artistic Director of The Duncan Dancers. She offers classes in the Duncan technique locally at the DC Dance Collective. Visit www.duncandancers.com for more information.

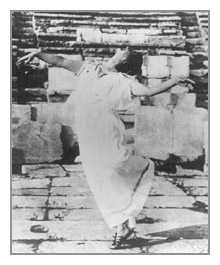

(image of Valerie Durham performing the work of Isadora Duncan)

thank you for the wonderful article!